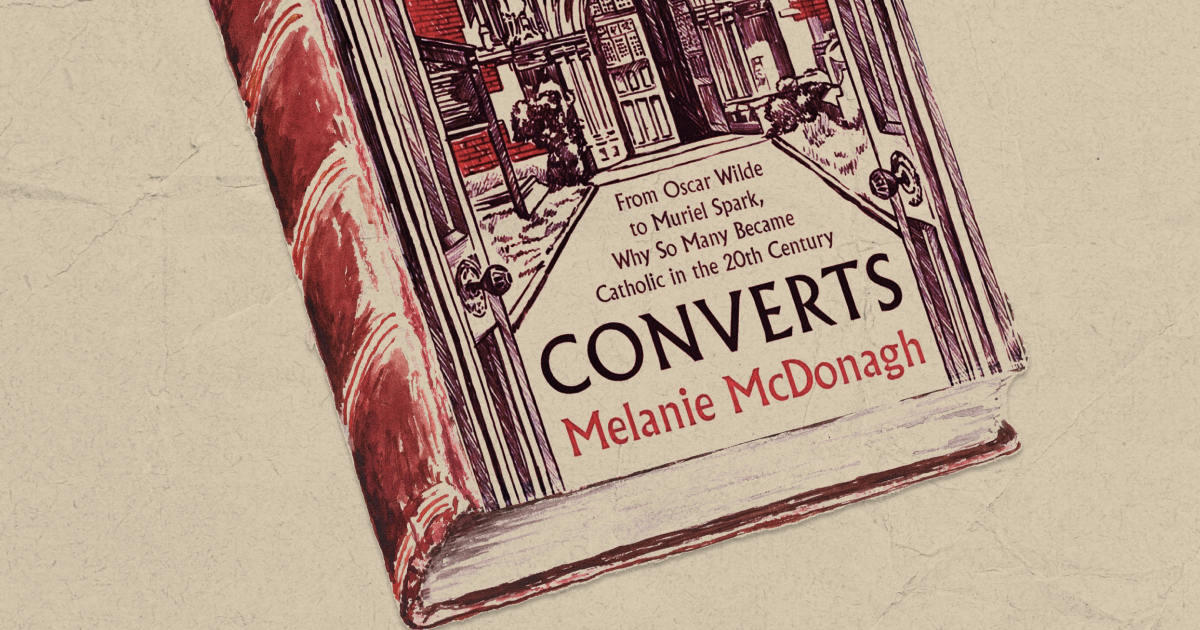

It is rare to know before reading an author’s first book that you will certainly enjoy it. But having read the insightful reflections of Melanie McDonagh throughout her prolific journalistic career, writing for the Spectator, The Telegraph, The Times and, of course, the Catholic Herald, it was a near certainty – the kind of certainty that the sun will rise tomorrow – that her first book, Converts, would be enjoyable.

Conversion to Catholicism is not a uniquely British phenomenon. From St Josephine Bakhita to Takashi Nagai, the rest of the world has its examples and, during the 20th century, the number of Catholics in sub-Saharan Africa grew by 6,708 per cent.

But there was certainly something particular about the wave of intellectuals, artists and writers – as well as thousands of ordinary Britons – who crossed the Tiber during the 20th century. McDonagh offers readers a chronological exploration of these conversions, beginning with perhaps the most eminent – and who only just made it into the period she examines – Oscar Wilde. His deathbed conversion in 1900 had numerous preludes throughout his troubled life and, like much of today’s British Catholicism, was influenced by Newman, whom he described as “the divine man”.

Newman’s influence appears in a great many of the converts treated by McDonagh. Hugh Benson, the son of an Archbishop of Canterbury who became a Catholic priest, said his conversion was due to “Newman, chiefly”, and Muriel Spark described hers as being “by way of Newman”.

Newman is also unusual in that his conversion not only provided the intellectual framework that enabled others to make the jump; it also created what has become a well-used bridge from Protestantism to Rome: Anglo-Catholicism. It would be utterly repugnant to Cranmer and Latimer that much of the reformed Church in Britain today defines itself by how closely it mimics Roman Catholic worship, with some attempting to embody it entirely. But thanks to Tractarianism – a movement founded by Newman alongside John Keble, Edward Pusey and Hurrell Froude – Anglicanism now places itself on a spectrum from “high” to “low”, with Anglo-Catholicism at the “high” end.

The Tractarians held that the one Catholic Church exists in three branches: the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Churches and Anglicanism. Thus the “protest” of Protestantism was over.

Many converts have come from Tractarianism, which McDonagh describes as a movement “to make the Anglican Church very much more like Roman Catholicism in outward forms, inward piety, architecture and institutions”. Its theology is intended to sit within the Anglican Communion, as it did for Pusey. But for others it became a stepping stone, as evidenced by the 900 or so Anglican clergy and religious who have become Catholic in the past 30 years. The book rightly devotes a full chapter to exploring its potency.

Other chapters cover the reliable and enjoyable set of British Catholic converts – many of them former Herald writers – such as G. K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene. McDonagh illuminates their stories with exquisite anecdotes and source material, including a letter from Waugh to his goddaughter Edith Sitwell on the occasion of her reception into the Church. In it, Waugh, a famously difficult man, writes: “I know I am awful. But how much more awful I should be without the Faith.” He also encourages Sitwell to “recognise the sparks of good everywhere” and mentions a “rousing sermon… against the dangers of immodest bathing dresses”, assuring her that they were “innocent of that offence at least”.

The liturgical changes of the 1960s, which reached their crescendo in the Mass promulgated by Pope St Paul VI in 1969, had a devastating effect on the number of conversions. Britain’s converts have often had a particular devotion to the Tridentine Mass, perhaps because their experience of other liturgical traditions fostered a deeper love for mystery and sacramentality. The desire to retain the Mass of the Ages was such that prominent Catholic and non-Catholic figures in British society petitioned Paul VI, who in 1971 granted an indult for the use of the Tridentine Mass in England and Wales.

Nonetheless, the number of converts fell dramatically. Fifteen thousand were received into the Church in 1960; by 1970 the figure had fallen to just over 6,000.

Yet McDonagh ends on a hopeful note, highlighting the “modest increase in numbers more recently” and observing that the “young show unexpected resilience in their attachment to the faith”.

This book, for convert and cradle alike, is essential reading for anyone wishing to explore the movements of the heart that have led so many interesting people to embrace Rome in the land of Mary’s Dowry.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)