If the future of the Catholic Church is to have a new lingua franca, there’s a good chance it may be Tagalog, one of the languages spoken in the Philippines.

The archipelagic country in Southeast Asia, which is already home to the largest Christian population in the Asian continent, is poised to reshape Catholicism's clerical landscape, especially when the homelands of Europe languish in vocational decline.

Ordination and seminary formation rates have been climbing steadily across the Philippine archipelago. While centuries-old seminaries across the globe struggle to meet minimum class sizes, Asia is bucking the trend with a 1.6 per cent rise in new priests and a narrow increase of 0.1 per cent in the number of women committing themselves to holy orders in Southeast Asia.

The Philippines is seen to lead this charge, with a Catholic community of over 93 million, comprising roughly 77 per cent of its national population.

The figures speak for themselves. While the rest of the world is watching its seminaries empty like a parish wine cellar after Easter Vigil, with even the oft-resilient Latin American Church slumping in the face of secularism, the Philippine Church is picking up the slack.

For Rome, the Philippines seems a perfect gift of providence. Offering a perfect blend of Asian orthodoxy and Western practicalities – English is one of the country’s official languages, and much of the country’s literate population is proficient in it – there is a natural cultural flexibility in the Philippines which serves Filipino seminarians perfectly as they go forth to preach God’s word.

Just as Ireland once supplied missionaries to Africa and to the Americas, while Poland quietly replenished German parishes in the 1990s, so now the Philippines stands poised to become the great modern exporter of clergy.

And no discussion of the Philippine Catholic influence would be complete without referring to Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, whose ascension from a humble metropolitan priest to Pro-Prefect of the Dicastery for Evangelisation has made him the most globally recognisable Filipino cleric in history.

The "Tagle factor", recently highlighted by the viral moments of the so-called People's Bishops seen throughout the recent papal conclave – ranging from belting out karaoke songs to delivering misty-eyed homilies to crowds on the streets of Manilla – has sparked much international delight and pushed the Philippines into the global Catholic consciousness. At the same time, Tagle's efforts to bridge Vatican structures with locally-rooted social concerns, along with his effusive presence, has made donning the cassock a viable career option for young Filipinos.

Indeed, when Tagle was appointed Archbishop of Manila in2011, the city’s diocesan seminaries saw their intake rise within two years – helped along by Tagle's habit of dropping in unannounced to talk, sing and pray with seminarians. By the mid-2010s, dioceses influenced by Tagle’s pastoral style reported double-digit percentage increases in philosophy-level entrants. And now, from his seat within the Vatican's hallowed halls, the prelate that many refer to as the Asian Francis is exporting that same inspiration on a global scale.

Over 60 per cent of the world’s seminarians come from the Asian or African continents. Thus, it speaks to reason that the next generation of Filipino priests will be at the forefront of our battle to revitalise a faltering faith.

The Philippines brings with it a cultural Catholicism unashamed of its vibrant processions, its vibrant Holy Week, its unabashedly energetic style of public worship. Where the Christian faith in the Western world seems to be shrinking in a timid whisper, the Filipino presence may reignite a more animated incarnational attitude – one that carries with it the scent of sampaguita garlands, made from the national flower of the Philippines, rather than the smells and bells of traditional European Catholicism.

This, of course, will not be without friction. The transplantation of a bright, fervent Catholic personality into post-Christian Europe may provoke as much pushback as acceptance. Parishioners used to by-the-numbers weekday Masses done in under 25 minutes may be gently scandalised by hours-long processions that blend Scripture, proverbs and the occasional joke.

But the beauty of Catholicism lies in its adaptability. From the shade of jackfruit trees to the sprawling cathedrals of Montreal and Milan, it is the Church’s propensity for scriptural universalism that can so often broach any cultural differences. And Filipino priests especially have been trained to preach anywhere and under any conditions.

If the 20th century belonged to the Irish missionary, the 21st may belong to the Filipino version: with a generation of priests trained in the humid intensity of Manila, yet still able to touch hearts in the damp of a rural Yorkshire parish.

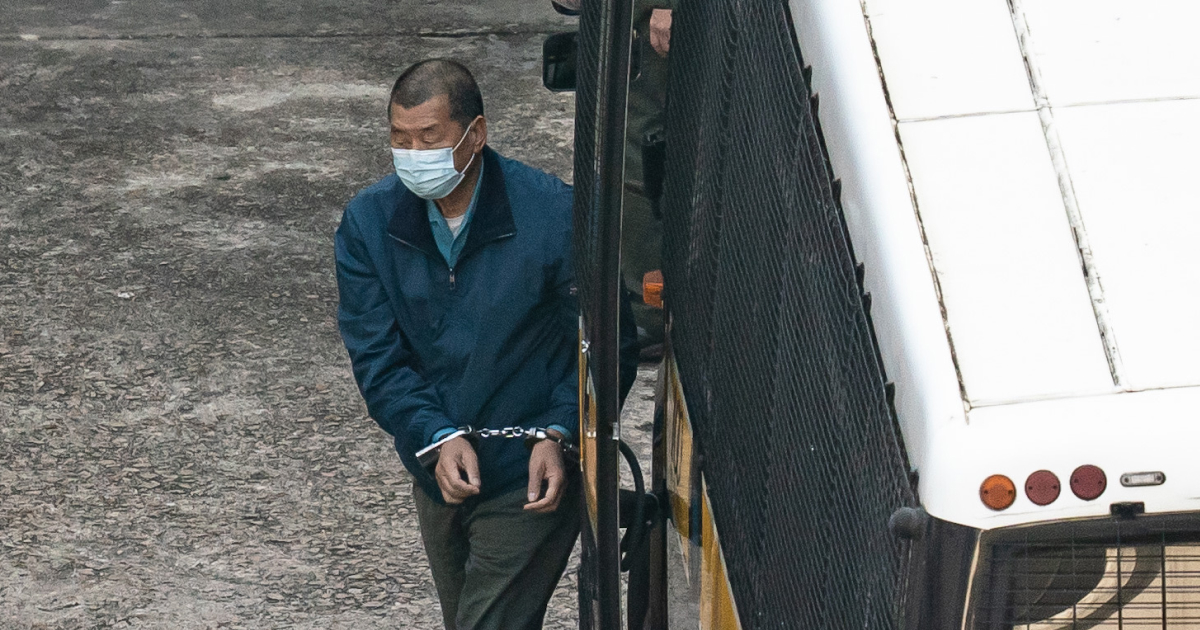

Photo: Seminarians attending a conference at the University of Santo Tomas (UST) Central Seminary in Manila, Philippines, 5 May 2025. (Photo by JAM STA ROSA/AFP via Getty Images.)

.jpg)