The Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors exhibition at the Gagosian (London W1, until August 25) is a burdensome proposal. To face a Picasso is already difficult enough, let alone one depicting a Minotaur, with all its Spanish connotations as well as its mythological ones.

The most startling series on show is 1935’s Minotauromachy, an intensely personal series for Picasso, shown here in eight pictures, which darken slowly from pale black and white, with the final one in faint colour. They depict a giant Minotaur, under which lies a wounded female bullfighter. The scene is lit by a candle, held by a young girl.

Picasso had ceased to paint at this stage, tormented as he was by his wife Olga Khokhlova’s refusal to grant a divorce, and his ambivalence over his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter’s pregnancy. The series also presages the oncoming Spanish Civil War of 1936, and his Guernica masterpiece, which also features a bull.

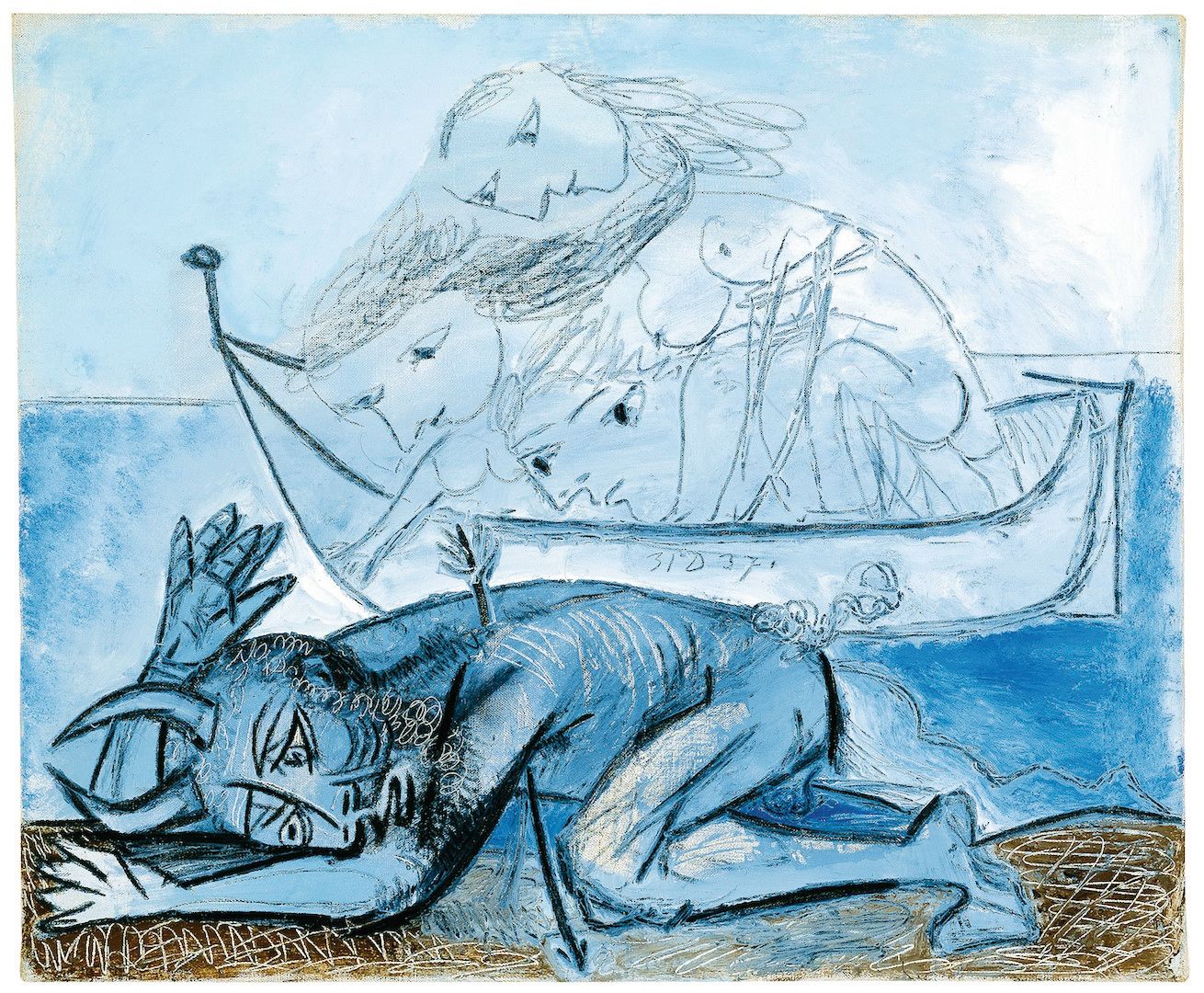

Picasso’s earliest and most notable encounters with Minotaurs were in his 1930-37 Vollard Suite – some of which appear in the exhibition. We see drawings of the half-man, half-bull grotesquely making love to a woman (who looks like Marie-Thérèse); or in Bacchic Scene with Minotaur, where it lies on a bed, accompanied by a man and two women, drinking wine. The intensely vivid, springy handling of pencil creates effective caricatures of the masculine figures, and of the prone women, who are twisted up around the arms of the grimacing machos.

Other pictures of the Minotaur, juxtaposed with gracile white women, create a strange sense of what Picasso is trying to do. These self-portraits create a feeling of alpha-maleness, of genius-to-the-point-of-freak that was doubtless familiar to him.

The most moving image is of the Minotaur looking with tenderness at his beloved as she sleeps – the brute with a fragile heart. Disney’s recent Beauty and the Beast film came to mind and I chuckled wryly at the low-brow pathos. For its elements of the Vollard Suite alone, this show is creaking with genius, and its sensitivity to ideas of what makes up a personality.

Meanwhile, at the National Gallery, Trinidad-based Brit Chris Ofili (notorious for his Catholic-baiting art) has painted the walls of the Sunley Room with a rather lugubrious sludge-coloured wash – with a surprisingly simplistic, Cézanne-inspired tapestry as the primary focus. Called Weaving Magic (on until August 28), the tapestry design would have been great had it been teeming with detail. Also, Sunley Room exhibitors seem no longer bound to take their inspiration from the National’s permanent collection, which seems a shame.

.jpg)