A century ago, an unknown Georges Lemaître arrived in Britain with an immense opportunity. Having studied mathematical physics in Belgium he had received his masters degree but it was not viable outside of his native homeland. Being granted permission and funding, he was given a place at St Edmunds College, Cambridge University to work for an upgrade to PhD under legendary mathematical physicist Sir Arthur Eddington.

Eddington was a scientist of huge reputation at the time, having made Einstein world-famous through his phenomenal proof of the German’s Theory of Relativity by taking photos of the 1919 eclipse from the tiny African island of Principe. The starlight surrounding the sun is bent from where it should be by the sun’s gravity in one of the most famous photos in the history of science. For Lemaître to gain the opportunity to work under his tutelage was an immense privilege, but he came with the recommendation of his peers and had published work of quality in Belgium. Eddington, himself a Quaker, was open minded enough to receive the priest-physicist and had a reputation for being welcoming and approachable with his students. After all, Eddington had been among the first to promote women in astronomy and was a true internationalist.

When Lemaître arrived, accommodation was found for him at St Edmunds House where records of his time there remain today and are prized by the University. Lemaître sought and found two other Catholics there in order to have daily mass. Dr Simon Mitton, life fellow of St Edmunds College at Cambridge University, committed Catholic, Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, and a tremendous writer in the history of astronomy has found Lemaître’s old chair which now bears his name. It remains in the possession of the Catholic chapel in the college as a memorial to his time there.

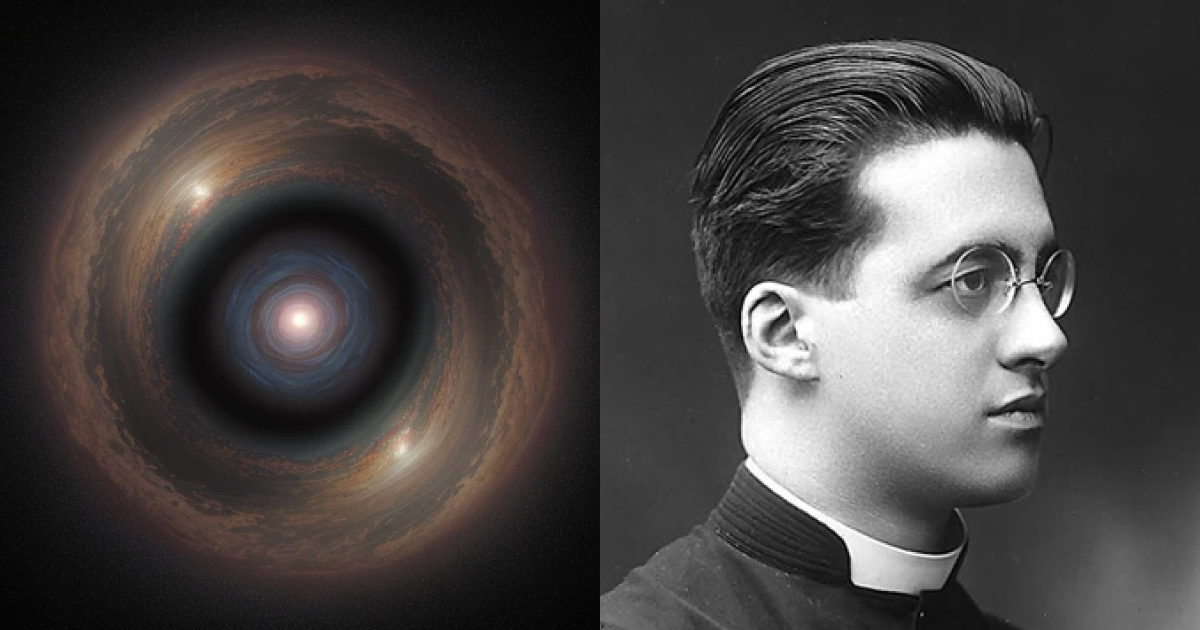

Set to stay only for a year, Lemaître developed his work on applying Einstein’s equations to the cosmos. He was one of very few at the time with the mathematical nous to take on such a challenge. It was not long before he (much as Alexandr Friedmann was doing across Europe) noticed the startling conclusion that necessarily followed Einstein’s equations: the universe must have emerged from a primordial state. This ‘singularity’ was a moment in the finite past. When Lemaître’s time in Cambridge came to an end he had built a strong relationship with Eddington and the two continued to collaborate.

Einstein himself had famously been repulsed by the idea of a beginning to the universe. In what he later called his “greatest blunder” he missed the Big Bang by introducing a fudge factor, allowing Lemaître and Friedmann to work it out themselves independently. When Lemaître made contact with Einstein to relay his mathematical work to him, he quipped to the German that “you seem to have contrived a day without a yesterday.” Again, Einstein remained sceptical until Edwin Hubble’s work at Mount Wilson Observatory in the USA on red shift light from distant galaxies proved that the universe was indeed expanding. There was now no means of fudging the numbers. Observation had indeed proved theory.

Here is where Lemaître’s relationship with Eddington from his year in Cambridge paid off immensely. Where Eddington had been applying relativity to astronomy in his own way, Lemaître leaned in and mentioned his own findings. They dialogued for weeks during a cross-Atlantic voyage where Lemaître disclosed his findings. Eddington was shocked that they had not been published when Lemaître explained that they had indeed been published years earlier – in an obscure Belgian journal in the Belgian language. Eddington hastily arranged for them to be translated into English and published in the proceedings of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Barely a year later, the first symposium was held on what was later to be called “The Big Bang” by Sir Fred Hoyle. Einstein, Eddington and Lemaître were all present and physics once again needed to reckon with groundbreaking findings in what had been a revolution in science since the First World War. First had come relativity, then the new quantum physics, and now the universe had a beginning. In 1931, Eddington wrote the first English language popular explanation of the Big Bang in his work The Expanding Universe. In it, he gives immense credit to Lemaître whilst also explaining his own unease with the thought of a “Big Bang”.

What followed was a miniature revolution all its own, where Lemaître had to reckon with the church’s attempts to reconcile his work with a literal reading of Genesis. It was not often easy for the priest-physicist who was most happy with his students in Louvain. After Eddington died in 1944, Lemaître was to become the first recipient of the Eddington Medal in astronomy for his work.

We can be extremely grateful historically that one hundred years ago, Monsignor Georges Lemaître ended up at St Edmunds College, Cambridge University. Circumstances aligned to put him with the most influential and open-minded astrophysicist of the time, one whose easy, British manner allowed for a strong working relationship with him. We can only speculate how things might have been otherwise, but as we approach the centenary of Lemaître’s most famous paper it can undoubtedly be called a victory for science.