When I profess my faith on Sundays, I raise my voice at “true God from true God … consubstantial with the Father” to rattle any Arians standing nearby (they are legion, and not always laity). Then I thunder on until I declare that I am looking forward to the Resurrection of the Dead.

In truth, I mentally pole-vault this because I find the Resurrection of the Dead frightening and incomprehensible. But in this season of Advent there is nowhere to hide. Behind the joyful invitation to welcome the Christ-child we are confronted with gospels warning week after week that it’s also the second coming of Jesus we are waiting for.

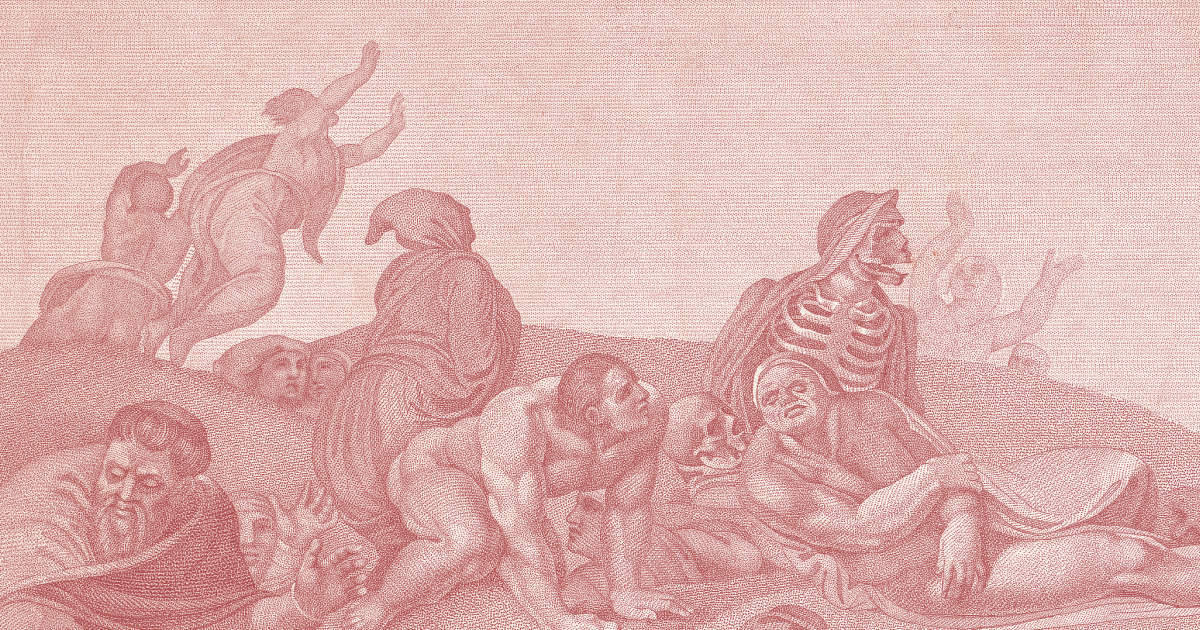

It’s not just the Last Judgement that I’m baulking at but the thought of rising among billions of bodies, naked and plastered against each other in a sweltering cacophony of fear, saved and damned alike. The great Renaissance frescoes show what it might look like, but not how it will feel or smell!

The consubstantiality of the created exists within time and space — my home ground. I am comfortable leaving the spiritual stuff to the realm of mystery, but our resurrection entangles the two. The incarnation in reverse. Jesus became human without relinquishing His divinity. On the last day we will become eternal without relinquishing our flesh. If I have to avoid thinking about the impossibility of shared chemical components being simultaneously utilised on the Day of Judgement, is this really my credo? But then I can’t compute how the universe has emerged from a single atom, invisible to the human eye.

The great frescoes of the Last Judgement repel rather than scare me. The very acts of human judgement which Christ forbade. Prophesying the fall of the mighty or lingering on the more salacious aspects of sin like a medieval version of the Sunday Sport. I suspect they engendered as much self-righteousness as fear in those who hadn’t participated in great excess. The wrath of God they portray has no place in the soteriology of those who focus exclusively on His mercy, but the gospels are uncomfortably uncompromising about this. The rejoicing in Heaven is about reformed sinners.

Those who unrepentantly hurt others will not be at the party. In fact the concept of mercy is meaningless outside the theatre of sin and punishment, and we all know sin. This distortion of our human and spiritual potential is the object of God’s wrath. How could it be otherwise? But we struggle with the tension between mercy and justice.

Those melodramatic judgement frescoes with their refined individual tortures owe more to Ovid than the teaching of Christ laid out in Matthew 25: “I was hungry, thirsty, a stranger, naked, sick or imprisoned, and you ignored me, averted your eyes, shrugged helplessly.” No amount of cinnabar, gold leaf or ultramarine can make that look sexy.

Perhaps that knowledge will be the worst punishment. No grand gestures were needed for salvation — just a steady drip of empathy and kindness. No terrible debauchery required for exclusion — just a comfortable indifference to those in need, shored up by a bit of casuistry. So the shepherd will separate the flock but He doesn’t tell us in what ratio. How fearful should we be?

The hill that Jesus chose to die on was the hill of outrageous mercy. It wasn’t his niceness that aroused fear and anger in his enemies. It was his embrace of those who had always represented real danger to Jewish survival. Samaritans whose apostasy diluted the purity of the Covenant. Adulterous women undermining the sanctity of the home and table where their faith had been preserved and passed on through exile and persecution. Those who colluded with the unclean invaders. Lepers, blind, and lame, who had clearly been marked out for punishment by God. No wonder his radical inclusion looked like the work of Beelzebub.

Jesus said, “Come in” to all who had been excluded to preserve the integrity of the chosen. We can’t hear how shocking this was unless we replace their transgressions with the most unacceptable of our own era. The mighty Judge of the Last Day — not blind and not interested in weights and measures — is the one who keeps trying to keep the door open. This is what the doctrine of the Incarnation with its thirst, blisters, nettle stings, weeping, bleeding, terror, betrayal and death attests to. He did it all to save sinners, not to condemn them. He didn’t go through all that to fail. He is almighty. The hill of outrageous mercy is the beacon of outrageous hope.

As we draw to the end of this Jubilee year, we do not come to the end of hope. Hope goes on till the day when we break out of the senselessness of death and burst back into the light. All the tricky, sticky stuff we leave to Him.

.jpg)