The philosopher Richard T Rorty posited that novels "let us know how people quite unlike ourselves think of themselves, how they contrive to put actions that appal us in a good light, how they give their lives meaning".

Reading novels, he thought, could be an exercise in spiritual development: an analogue to Bonaventure and Thomas à Kempis.

He explains: "The problem of how to live our own lives then becomes a problem of how to balance our needs against theirs, and their self-descriptions against ours."

In 2007, American writer Nalini Jones published her debut collection, What You Call Winter, a series of interlinked stories that dramatised the lives of Catholics in Bombay the book was based, in part, on her mother's life there. The writing was lush, but story collections are hampered by brevity. Readers often want more depth.

Now Jones returns with her first book, The Unbroken Coast, and Catholics are again her subject. Here form meets function: Jones was born to write novels. Set again in a Catholic enclave in Bombay, the story spans from 1640 to 2005, and is over 450 pages long. Its final act is riveting and heartbreaking.

Jones is a gifted prose stylist. Neither baroque nor brusque, she writes gorgeous sentences that reward a reader's attention. Bombay is magically rendered. From the sea, the city "coalesced to a bit of coastline" that a character could "blot out with his thumb". Yet on land, it was "a multitude of cities, infinite cities, shimmering one on top of the next".

It was a city "coursing with people. The city held them all in her huge cupped hands: gamblers and pilgrims, migrants and Maharashtrians, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Catholics, Parsis, Jains, Sikhs and Jews ... How could you untangle what had twined together over centuries?"

Tradition is Jones's central thematic concern. In the 17th century, a statue was dragged from the sea: "Her robes looked nearly black, and her face was obscured by the veil of the net. Yet they knew at once who she must be."

Mary remains a presence in the contemporary setting of the novel. Francis Almeida, an emeritus professor of history, is first introduced riding his bicycle "toward the shrine of Our Lady of Navigators" at "eleven at night, a ridiculous hour for cycling, according to his wife".

His bicycle is not merely a means of locomotion; Jones depicts Francis as a man continuously pulled toward his youth, despite his advancing age.

Francis has just been named chair of the local historical commission. He enjoyed the work, having written a history of the local parish, but his wife was sceptical: she "understood [the historical commission] as a way for Francis to earn no money while being of no help to his wife and no use to his family".

Yet Jones feels for Francis's wayward state: "Since his retirement a few months before, his days felt like a series of empty rooms he must wander through, one after another: classes he would never teach, children who had gone and grandchildren he would seldom see. The future would be lonelier than the past. But he could stand where others had stood, swept up in currents of history."

Francis is equally drawn to his own history; his first love tragically died near her 20th birthday, and he soon fell for her sister – but saving a photo of his first love to the present.

Although the cast of The Unbroken Coast is widely compelling, the other most central character is Celia, a self-aware young girl who has a chance encounter with Francis that leads to a familial connection: "Celia knew she was not beautiful – she had a forehead like the beach at low tide and a chin like a double knot."

Her father is a fisherman. "All her life," Celia reflects, "her father had gone to sea; all her life, her mother had listened to forecasts. But on nights like this one – smoky , moonless, the stars old and faded – Celia could not discern between sky and water to find the horizon. There was only a great rolling darkness, with no map lines to score it."

In the same way that sea and sky become one, past and present meld in Jones's keen novelistic hands.

Jones reveals her literary talent in the grand moments of The Unbroken Coast, but also in more subtle ways. Writing about the local Catholic school, Holy Name Primary, she notes that the school's uniform was a way to cultivate culture:

"In proper shoes, girls greeted each other; in proper shoes, they shared the scarred wooden benches of the classroom; in proper shoes, they ran laps around the courtyard with Miss Pinto at their centre, consulting her stopwatch."

Richard Rorty thought that certain novels could offer readers "a sense of exaltation" similar to "religious people who come away from reading devotional literature with a sense of having visited a better world".

He was speaking of Marcel Proust and Henry James, but we can surely add Nalini Jones to that list.

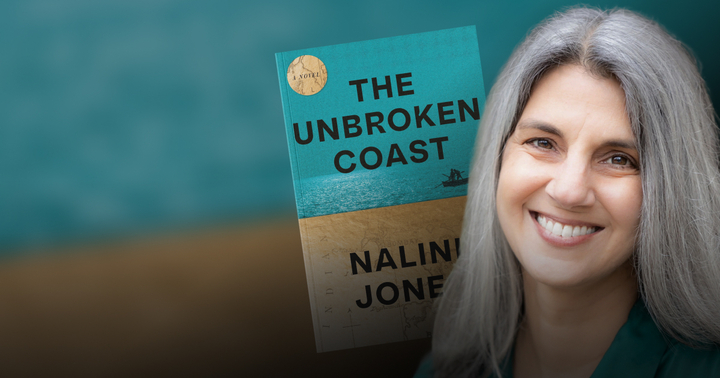

Photo: graphic with Nalini Jones (credit: Arcadia)

The Unbroken Coast by Nalini Jones is out now (Knopf, £25)

This article appears in the September 2025 edition of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre and counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click HERE.

.jpg)