In Ireland, publicly funded education is almost entirely Catholic and this, from a Catholic perspective, is no longer a good thing.

To safeguard the integrity and Catholicity of the education being provided to Catholic families, the Irish bishops must divest the majority of these schools.

The two primary reasons to do this are that the status quo is not serving the mission of the Church, and that we do not have the resources to ensure that each of these schools is committed to witnessing to the fullness of the Faith. You could add a third: if we do not act now, our hand will be forced in the future.

By way of background, at present some 98 per cent of publicly funded primary schools for children aged five to thirteen, and just over half of secondary schools for those aged thirteen to eighteen, are under the patronage of the local bishop and or certain religious orders.

There are obvious historical reasons for this. When the Irish State came into being a century ago, it was poor and overwhelmingly Catholic. It was natural that the Church, already heavily involved in education, should step in to fill gaps the State could not itself provide.

The landscape is now entirely different. The State’s resources have increased, while the Church’s have diminished, both financially and in terms of the number of believers. Census data shows that Catholic affiliation has fallen to 69 per cent, down from 79 per cent in 2016.

Mass attendance and voting patterns on issues such as abortion are even more concerning, indicating that a significant majority of Ireland are no longer convicted Catholics who practise and believe the fullness of the Faith. In 2018, 66.4 per cent voted in favour of abortion, and recent estimates suggest that just 35 per cent of those identifying as Catholic attend Mass weekly.

An ongoing government run survey of parents on the question of patronage has brought this issue to the forefront of public debate. This is the third attempt in four years by Irish politicians to drum up a mandate for change in the patronage of state schools. Previous surveys have indicated that parents prefer the Catholic ethos, and there is little reason to doubt that the 2025 iteration will prove any different. However, the primary reason parents prefer Catholic schools is not the witness they give to Christ, but academic excellence.

It is ironic that a rare indication of trust in the Church is also largely bad for the Church’s mission, which is to foster an encounter with the person of Christ. Despite the Church’s near monopoly on educational provision in Ireland, the Church is shrinking. Many of our cultural elites, themselves products of Catholic education, are hostile to the Church and poorly informed about it. Those who remain in the Church repeatedly profess themselves ill prepared to speak about their faith in any meaningful way.

Not all of this can be blamed on Catholic schools. But it is difficult to argue that Catholic education is effectively forming the faithful in matters of faith and morals when this evidence is taken as a whole. This is not to suggest that teachers and staff do not work hard to provide a good Catholic education, however, when the number of teachers and principals who are intentional, practising Catholics is declining, something highlighted across almost every metric in the 2024 GRACE project report on Catholic education, a clear succession concern emerges. Inevitably, the effectiveness of their witness is diluted when they are spread across schools in which the majority increasingly do not believe or practise the Faith.

Quite simply, we do not have the resources to sustain the number of schools currently under Catholic patronage.

As a result, instead of providing a profound and rigorously Catholic education, Catholic schools are forced to compromise on integral aspects of the Faith. The net effect is that the needs of intentional Catholic parents are set aside in order to cater for all.

While it is sometimes argued that divesting schools will abandon those on the fringes of the Faith, the reality is that by the time many students leave school, they do not understand the Faith, and what little they do know is often so bland and incoherent that it is either rejected or forgotten.

From my own experience as a secondary school graduate in 2015, religious education classes functioned as de facto free periods, or as diversions in which we were taught Tai Chi or shown videos about world religions. The only time I recall discussing the Bible was when our Mass going RE teacher attempted to argue in favour of gay marriage. Later, while studying for a Master’s degree, my classmates, all products of Catholic education, were astonished to discover that the Church still teaches against the use of contraception. These are small examples of a wider problem: graduates of Catholic schools are neither catechised nor evangelised effectively.

The most effective response is to concentrate resources on a smaller number of schools. Doing so will require courage, foresight, and careful planning from the bishops, particularly to ensure that the needs of the poor remain central throughout the divestment process.

But in the long term, it is in the best interests of the Church to have schools that provide a firm grounding in the truths of the Faith and a profound witness to Christ’s loving care for each student.

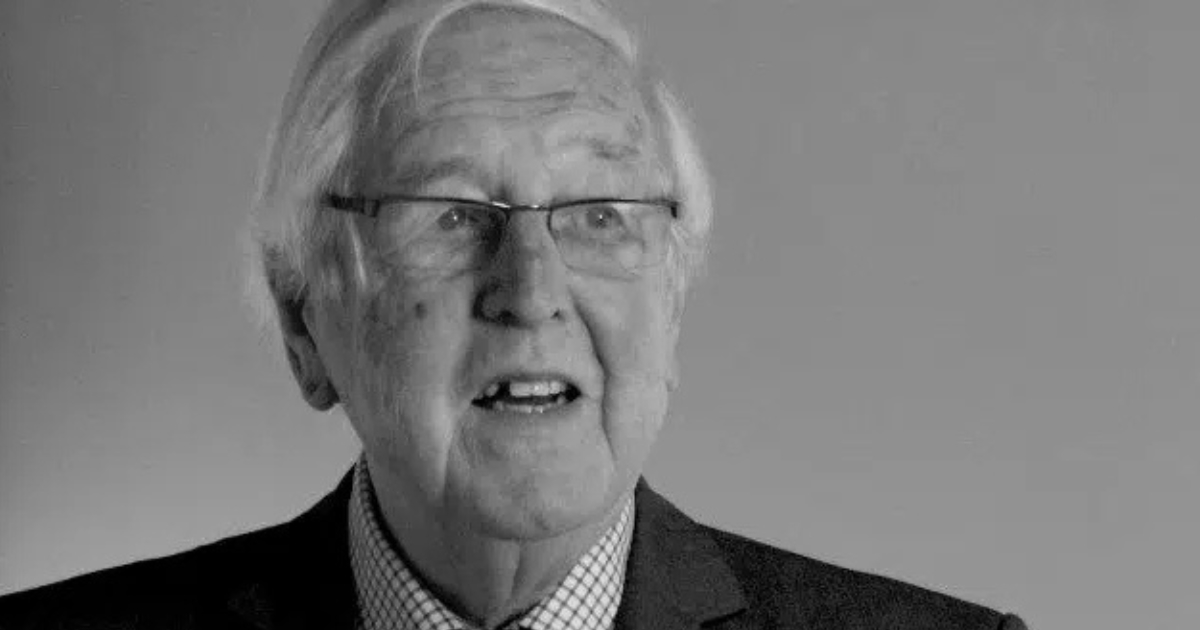

There is also a further pragmatic reason for divestment. In a recent interview, the Primate of All Ireland, Archbishop Eamon Martin, said that parishes and schools should prepare for the possibility of future hostile secular governments. Furthermore, only three years ago a group of Catholic scholars warned in the Irish academic journal The Furrow that if the Church does not act now on divestment, a hostile government in the future will force its hand.

That is yet another reason to act decisively while there remains an opportunity to negotiate a settlement that serves the mission of the Church.

.jpg)