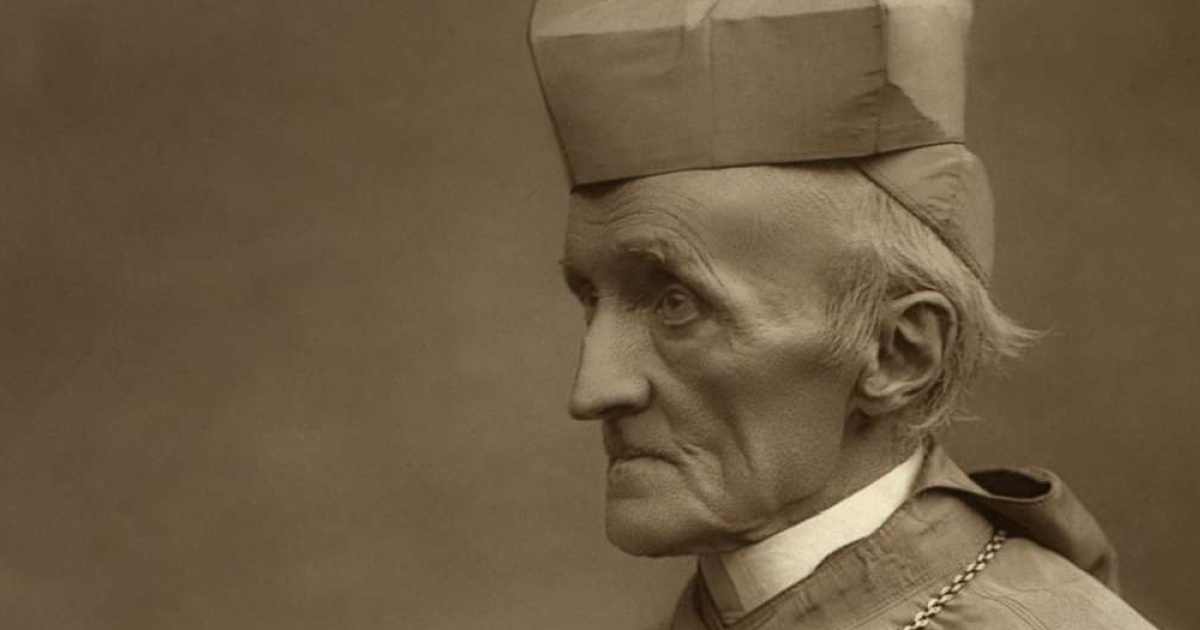

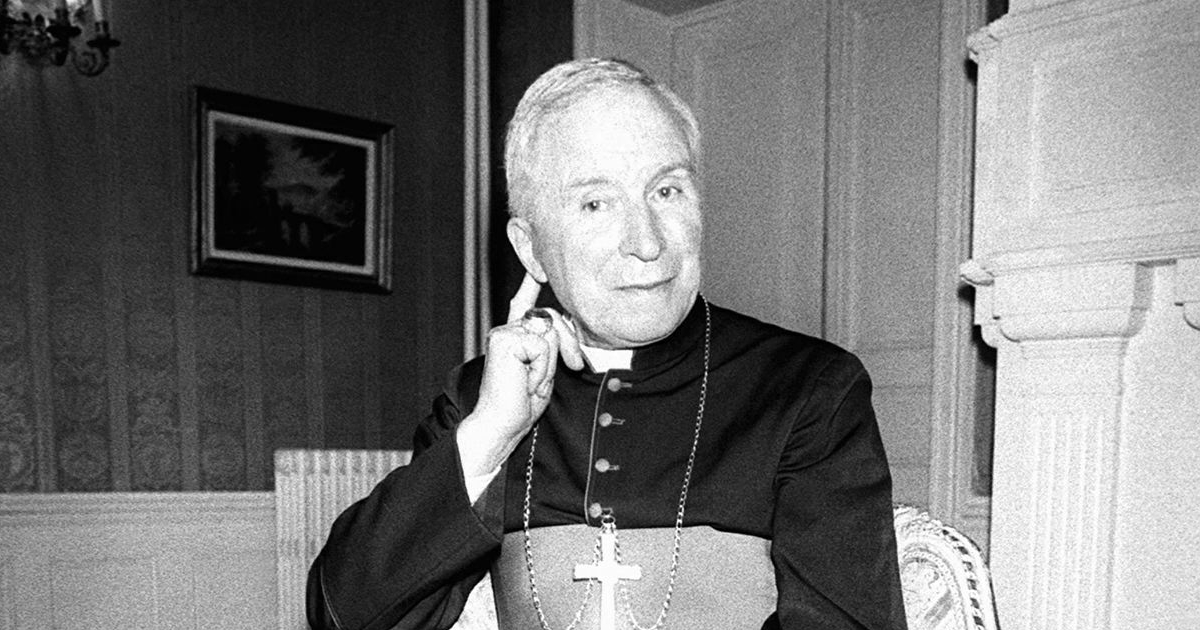

2026 marks 175 years since Henry Edward Manning’s reception into the Catholic Church on 6 April 1851 (Easter Sunday) and, within ten weeks, his ordination on 14 June at Farm Street on the Feast of St Basil the Great. He was to become the second Archbishop of Westminster and later a Cardinal. Hilaire Belloc described him as “the greatest Englishman of his time”, and yet has anyone of such greatness suffered so grievously at the hands of his biographers?

But first, the antecedents of this remarkable Englishman. Henry Manning was born at Totteridge, Hertfordshire, on 15 July 1808, the third and youngest son of William Manning, a West India sugar merchant, MP and Governor of the Bank of England, and Mary (née Hunter), of French extraction. One of his godfathers was Henry Addington, Prime Minister from 1801 to 1804 and by then Viscount Sidmouth, ironically a staunch opponent of Catholic Emancipation.

Young Henry enjoyed his boyhood at Coombe Bank, Sundridge, Kent, in the company of Charles and Christopher Wordsworth, later bishops of St Andrews and of Lincoln, nephews of the poet William Wordsworth. He attended Harrow with Charles and another celebrated Victorian, Anthony Trollope. At Balliol, where he earned a First in Greats, his friend and contemporary William Ewart Gladstone described him as “one of the three handsomest men at Oxford. He was not at all religious.”

A fall in the East India trade, which led to his father’s bankruptcy in 1831, awakened the spiritual side of Henry’s life. He was ordained to Anglican orders the following year and took up a seemingly obscure curacy at Lavington and Graffham, near Chichester in Sussex. There he met and fell in love with Caroline, one of the beautiful daughters of the ailing rector, John Sargent.

After a short betrothal and John’s death, they married and Henry assumed the living at Lavington. He tried to visit his parishioners regularly, many of whom were Downland shepherds, and became a familiar and stately figure trudging the country lanes.

But tragedy struck as Caroline succumbed to the family curse of consumption and died on 24 July 1837, aged 25, leaving Henry a childless widower. His most compellingly readable, but also most malevolent, biographer, Lytton Strachey (Eminent Victorians, 1918), claimed the death was a convenient one and that his dead wife was henceforth blotted out of his life.

In fact, he found it too painful to speak of her. It was said that a flower would be taken from Caroline’s grave every year and received by the old Cardinal with great emotion. Around his neck he continued to wear a chain with a locket containing an image of Caroline. As he was dying in 1892, he entrusted, from under his pillow, a volume of his wife’s prayers and reflections to his successor, Herbert Vaughan, saying: “Not a day has passed since her death on which I have not prayed and meditated from that book. All the good I may have done, all the good I may have been, I owe to her.”

For some years Caroline’s mother cared for him as he, with the iron will, self-denial and relentless activity that appeared to possess him, carried out his pastoral duties. He then saw the Anglican Church as the via media between the corruptions of Rome and the heresies of continental Protestantism, and, although never a disciple of John Henry Newman’s, he undertook to become a distributor of the Tracts for the Times in his locality.

In the winter of 1838, he joined Gladstone in Rome, the first of twenty-two visits Manning would make to the Eternal City. While there, they both called upon the rector of the English College, Nicholas Wiseman, who would become a major figure and patron for Manning.

He was becoming a national figure in the Church and in 1841 was made Archdeacon of Chichester. As John Henry Newman moved closer to Rome, Manning continued to hold the High Church line. Like Newman, he could fill St Mary’s, Oxford on a weekday, and he preached a strongly anti-papal sermon there on Guy Fawkes’ Day 1843, to Newman’s distress.

Manning saw John Henry’s secession in October 1845 as a failure of loyalty to the Church of England and “a dangerous lapse into Romanism”. But he soon felt his own position untenable. In December 1845 he was offered, and declined, the post of sub-almoner to the Archbishop of York, seen as a springboard to a bishopric.

In February 1847 he fell seriously ill and spent ten months abroad, much of them in Rome, where he had an audience with Pius IX. He returned to England still undecided.

He has been accused, in two volumes, by his first major, and lamentably unsuitable, biographer, E. S. Purcell (1896), of remaining an Anglican after losing faith in its teachings, and of becoming a Catholic for motives of worldly ambition. This palsied view was reinforced and popularised by Strachey in Eminent Victorians.

David Newsome, in his magisterial entry on Manning in the Oxford DNB, has proposed a fairer view, recognising “that he could not contemplate injury to the church whose preferments he had accepted, and the sorrow caused to those near to him, until his doubts had become certainties. This eventually came about through an escalating series of considerations and events…”

A catalyst was a decision of the Privy Council on 8 March 1850, overruling the Court of Arches, concerning George Cornelius Gorham, who had been refused a living on account of his unorthodox view that baptism was not a sacrament of regeneration. When only eighteen hundred, of a potential ten thousand, clergy supported his petition, Manning became convinced that the Church of England was no branch of the Church Catholic. And yet he was still resisting joining Rome. “Three hundred years ago,” he said, when the suggestion was made, “we left a good ship for a boat. I am not going to leave the boat for a tub.”

The secession of Mary and William Wilberforce in June 1850 was quite a blow. Then, later that year, Pius IX proclaimed the restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England. As Archdeacon, Manning was required to convene his clergy to register their outrage. He summoned the meeting, but vacated the chair and at Michaelmas announced his intention to resign.

On Easter Sunday 1851, with his friend James Hope-Scott, he was received into the Roman Catholic communion by Father Brownbill SJ at Farm Street.

“After this I shall sink to the bottom and disappear,” Manning observed to Robert Wilberforce. Loss of friends distressed him, as did his loss of influence in high places. But when a member of the Cabinet told him in 1854 that, had he remained an Anglican, he would have gained the bishopric of Salisbury, his reaction was: “What an escape my poor soul did have.” As the historian A. N. Wilson put it in The Victorians (2002), Manning was “one of the few establishment figures who had dared to leave the establishment.”