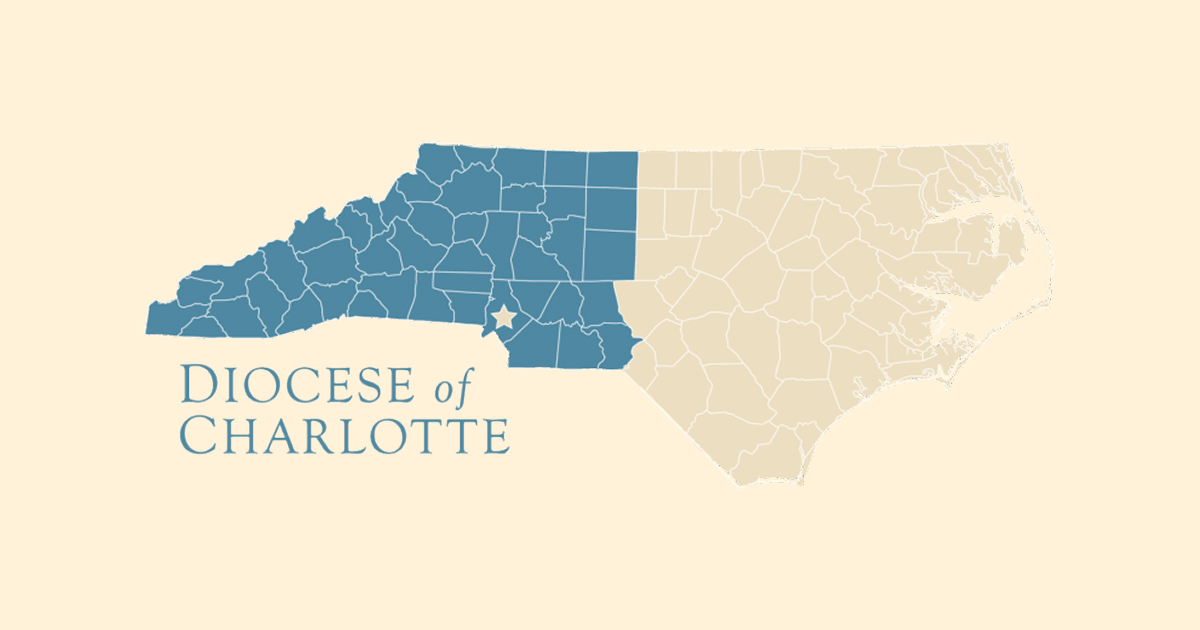

Thirty-one priests of the Diocese of Charlotte have submitted a series of dubia to the Dicastery for Legislative Texts, requesting clarification on whether the recent liturgical measures announced by their ordinary are lawful.

The appeal follows a pastoral letter issued last month by Bishop Michael Martin, in which he announced that altar rails, kneelers, and prie-dieus would no longer be permitted for the reception of Holy Communion in the diocese from early 2026. Parishes were instructed that temporary or movable fixtures used for kneeling must be removed by 16 January.

In an accompanying letter, the priests said that both the December pastoral letter and a policy draft that circulated unofficially last summer “have caused a great deal of concern amongst the priests and faithful of the Diocese of Charlotte, especially in those parishes that have allowed the faithful to use an altar rail or prie-dieu for the reception of Holy Communion”. The leaked draft, though never promulgated, reportedly proposed restrictions on Roman style vestments, altar crucifixes and candles, the use of Latin, and the recitation of traditional vesting prayers.

A central question raised by the dubia is whether a diocesan bishop may prohibit the erection of altar rails or order the removal of those already lawfully in place. The priests cite the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, which states that the sanctuary “should be appropriately marked off from the body of the church either by its being somewhat elevated or by a particular structure and ornamentation”, and adds that attention must be paid to “the traditional practice of the Roman Rite” rather than “private inclination or arbitrary choice”.

They argue that, as altar rails have long constituted a recognised structural marker of the sanctuary within the Roman Rite, clarification is required as to whether a bishop has legitimate authority to ban them outright. A related dubium asks whether the bishop may forbid their use in parishes where the rails already exist and are used by parishioners to receive Communion.

Another question concerns the provision of kneelers for members of the faithful who wish to receive Holy Communion kneeling. The priests note that the General Instruction explicitly permits kneeling and ask whether a parish priest or rector may, as a pastoral provision, place kneelers to accommodate those who choose that option “of their own accord”.

Further, the dubia address whether a diocesan bishop may prohibit priests from wearing particular styles of vestments that are not otherwise forbidden in Church law, and whether Communion by intinction (where the host is dipped into the precious blood by the priest before reception by the communicate) may be banned despite being explicitly referenced as an option in the General Instruction. The letter also queries whether a bishop can suppress liturgical prayers, gestures, chants, or ornaments on the grounds that they are commonly associated with the pre conciliar celebration of the Mass, in light of provisions affirming traditional practices.

A diocesan source has confirmed that the number of active, incardinated priests eligible to sign the letter is 83, rather than the approximately 130 listed in the diocesan directory, which includes visiting clergy and members of religious orders. On that basis, the 31 signatories constitute nearly 40 per cent of the diocese’s active priests.

The submission of dubia by a substantial number of diocesan priests to Rome is not merely a protest against local liturgical directives, but a test of the balance between episcopal governance and the limits imposed by universal law and tradition. The Church’s liturgy is not a private possession of any one bishop, generation, or ideological moment. The way Catholics worship shapes belief itself, lex orandi forming lex credendi, and decisions taken in one diocese increasingly echo far beyond local boundaries. The Charlotte case exposes a deeper anxiety about coherence and trust within the Church’s sacramental life.

The word dubia, the plural of dubium, comes from the Latin for “doubts”, but in ecclesial usage it is better rendered as “questions seeking clarification”. A dubium is a formal request addressed to a dicastery of the Roman Curia, or in some cases directly to the Holy Father, asking how Church law or teaching should be interpreted in a concrete situation.

Far from being rare or exceptional, dubia are a routine part of how bishops interact with Rome. They are most often submitted by bishops or episcopal conferences, though canon law does not restrict their use to the hierarchy alone. When a dicastery responds, it does so through a responsum ad dubium, often framed simply in the affirmative or negative, accompanied by a brief explanation. Crucially, such responses are frequently private, limited in scope, and authoritative only for the case at hand unless issued as a formal public instruction.

The decision of Charlotte priests to seek clarification from the Dicastery for Legislative Texts represents a serious recourse. Their questions concern whether a diocesan bishop may prohibit altar rails, kneelers, certain vestments, or legitimate options for the distribution of Holy Communion that are explicitly permitted by universal liturgical law. The outcome would matter well beyond North Carolina, although most dubia responses are private and not universally applicable.

Much will now depend on how Rome chooses to respond. The appeal from Charlotte places the Holy See at a fork in the road. It can intervene to restrain what many priests regard as an overreach, thereby assisting a diocese unsettled by rapid change, or it can allow Bishop Martin’s liturgical programme to proceed largely unchecked. For Pope Leo XIV, the handling of this case will be an early test of how seriously Rome intends to police the boundaries of liturgical law and episcopal discretion.