The Priestly Fraternity of Saint Pius X is facing renewed questions about its future leadership, as senior figures acknowledge that the ordination of new bishops will be necessary in the coming years.

Speaking on 8 December to the German outlet Corrigenda, Father Franz Schmidberger, former Superior General of the SSPX, said that discussions were under way but that no decisions had yet been taken. “It is being considered, but I cannot say when it will take place and how many bishops will actually be ordained,” he said.

Father Schmidberger said that any move towards new episcopal consecrations would require engagement with the Holy See. “The Society will have to discuss this with Rome, which is an essential point, because in a normal situation, bishops cannot be consecrated without the Pope’s permission,” he said. His comments come as the Society’s two remaining bishops, Bernard Fellay and Alfonso de Galarreta, approach their seventies.

Father Schmidberger underlined the practical implications of episcopal succession, stating that “only a bishop can ordain a priest”. Without bishops, the Society would eventually be unable to continue priestly ordinations.

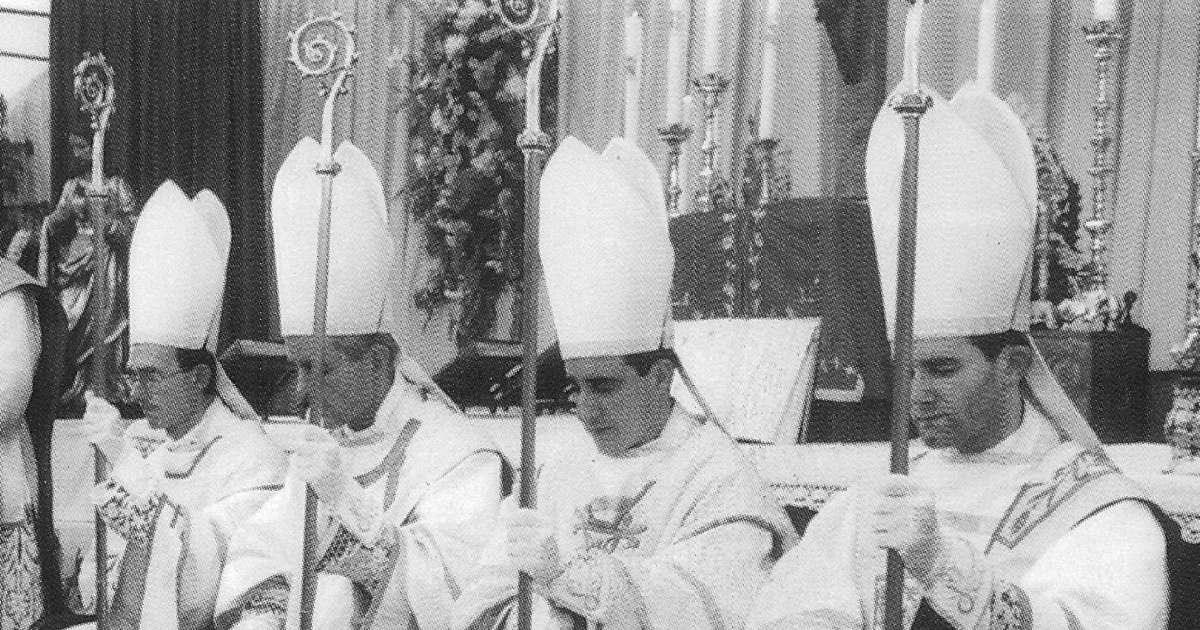

Discussion of future consecrations has also revived attention to the events of 1988, when Archbishop Lefebvre consecrated four bishops without papal mandate. Father Schmidberger said, “There was a crisis situation during the episcopal consecrations in 1988.”

He defended the decision taken at the time, saying, “It was the right decision, and the right way to execute it at the right moment.” He said the aim had been to offer “a public testimony to the ancient, traditional liturgy and the teachings of the Church”, which he believed were under threat. He added that the intention was to preserve Catholic life and practice and to “rebuild and renew it, just as monks and monasteries have always done in the Church”.

Father Schmidberger explained that any future bishops consecrated by the Society would not hold territorial authority. He said a bishop exercises both sacramental and juridical functions, and that any consecrations would follow the model used previously. Auxiliary bishops, he said, would be consecrated without jurisdiction, with responsibilities limited to ordaining priests, administering Confirmation, and consecrating churches and sacred vessels.

The Society remains without a regular canonical status within the Church. Asked about the possibility of full integration under Pope Leo XIV, Father Schmidberger said, “We consider ourselves fully integrated into the Church.” He added that whether this would be recognised juridically was uncertain and would depend on future developments. “Exploring this is the task of the Superior General of the Society and his council.”

Addressing criticisms of the 1988 consecrations, Father Schmidberger pointed to historical precedents in which bishops were consecrated without papal permission in exceptional circumstances, particularly in communist countries. “In extreme cases, it is possible to consecrate bishops without the Pope’s knowledge,” he said, noting that such cases were later acknowledged by Rome.

The interview reveals much about the long drama of authority, continuity, and crisis within the modern Church. Understandably, the SSPX hierarchy would want new bishops to continue their ministry, as the SSPX now has over 700 priests. A community of this size cannot exist indefinitely without a clear path of apostolic succession.

Removed from theological polemic, this alone explains why the Society is looking towards episcopal succession. For its survival, it needs bishops to ordain priests, confirm the faithful, and support the community’s sacramental life. As the two remaining SSPX bishops approach their seventies, this increasingly appears imperative for the Society.

To understand the situation, it is necessary to understand the long road that led the Society to the 1988 consecrations and, most importantly, the mindset of an SSPX priest formed in the decade before.

An SSPX priest formed under Archbishop Lefebvre would have been trained in a doctrinal world that appeared stable and continuous with Trent. Sudden changes in discipline, theology, and liturgical expression following the Second Vatican Council would have marked the beginning of that priest’s journey. The 1975 legal suppression of the Society, looming in the background, naturally produced disorientation and, in some cases, mistrust. When Archbishop Lefebvre faced cancer in the 1980s, many priests believed that episcopal succession was necessary simply to continue the ministry they had been ordained to serve.

Their seminarians had been raised on the Church’s theological memory, including the story of Saint Athanasius, who consecrated bishops without papal mandate during the Arian crisis. Seen from within that frame, the 1988 consecrations appear less like defiance and more like a desperate attempt to preserve a priestly identity during a period perceived, from an SSPX perspective, as doctrinally unstable.

Father Franz Schmidberger referred to this in the interview when justifying the circumstances of the 1988 consecrations. If one accepts the Society’s premise that its mission is to safeguard what it calls “Eternal Rome”, the logic becomes intelligible.

Yet today the question is different. The SSPX is no longer a fragile remnant but a vast global priestly body. While its bishops are ageing and its growth continues, its informal status cannot substitute for juridical clarity indefinitely. Whether Rome will grant a mandate is uncertain, but the Society believes itself already within the Church, even if not legally recognised, and therefore entitled to episcopal oversight within its spirituality.