Germany’s Christmas markets opened this year under the tightest security seen in peacetime Europe, as authorities attempt to maintain festive spirit amid fears of fresh political and religious violence.

Federal and regional authorities have instructed cities to reinforce entry points, expand surveillance and increase the presence of armed police and private security staff throughout the Advent season. The measures follow last year’s vehicle attack in Magdeburg, in which six people were killed and more than 300 injured.

In Magdeburg, where Taleb al-Abdulmohsen drove a rented BMW into crowds near the city hall, the market now operates behind strengthened barriers and controlled access gates. The market was briefly halted on the opening day of the attacker’s trial until officials confirmed that additional protective structures were in place. Investigators say Abdulmohsen, an ex-Muslim who had turned violently against his former religion, acted alone.

Security services continue to warn that jihadist groups remain active. The attack at Berlin’s Breitscheidplatz in 2016, in which Islamic State sympathiser Anis Amri murdered 12 people with a hijacked lorry, remains a reference point for counter-terrorism planning. According to The Times, a senior official said, “Daesh and al-Qaeda are still out there. They’re still trying to inspire people to commit terror attacks in their name.”

Several cities have adopted “digital twin” simulations to test layouts for weak points and calculate evacuation routes. Dresden has spent millions strengthening access protection at the Striezelmarkt. In Augsburg, the Christkindlesmarkt is surrounded by 450-kilogram concrete blocks known as pitagons, moved at intervals to allow trams to pass. Osnabrück has sealed off large parts of its city centre to vehicle traffic. Smaller municipalities report similar requirements but fewer resources; some near Hamburg have been instructed to hire professional security personnel for the first time.

Markets in Cologne, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Leipzig and other major centres now operate with reinforced entry controls, CCTV systems and mixed patrols of police and private guards. In several locations, barriers have been disguised with paint or seasonal decorations to reduce their visual impact. Despite the increased restrictions, markets across the country have opened as scheduled. Authorities say the measures will remain in place through December and will be reviewed after the season.

These developments, though focused on immediate safety, have also reopened a broader debate about the pressures shaping modern Europe: migration policies, social cohesion, religious identity and the quiet unease that increasingly surrounds public expressions of Christian culture.

While each attack has its own circumstances, together they have created an atmosphere in which Europeans now expect violence at festivals that once symbolised communal joy. The heavy defences surrounding Christmas markets signal not only credible threats but a deeper anxiety about the continent’s ability to absorb the changes it has undergone.

That anxiety cannot be separated from Europe’s long-running difficulty integrating large numbers of newcomers. For years, governments admitted migrants without developing the social, cultural or spiritual structures needed to receive them well. This gap has produced fragmentation and inconsistency, leaving some communities vulnerable to alienation and, in rare but serious cases, to radicalisation. The pattern is not universal, nor does it implicate migrants as a whole, but it exposes a system unable to sustain the moral and cultural foundations that integration requires.

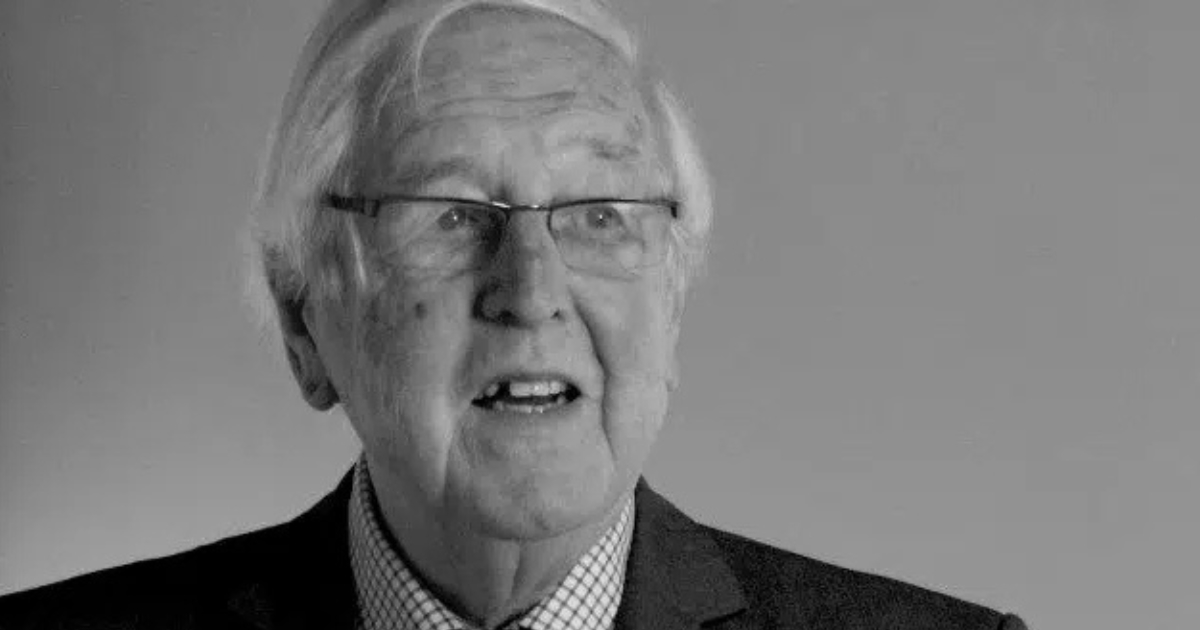

This vulnerability is intensified by Europe’s growing uncertainty about its own identity. A secular-progressive outlook dominant in many institutions encourages nations to downplay their Christian heritage and to treat public expressions of that heritage as divisive. In such a climate, Europe struggles to articulate why its traditions matter at all. As the philosopher Roger Scruton warned, a civilisation that grows uncomfortable with its own cultural home becomes susceptible to what he called oikophobia: a tendency to distrust or discard one’s inheritance.

A society that doubts the value of its own religious and cultural roots cannot easily invite newcomers into them. The result is a weakened shared identity, which in turn weakens integration and heightens fragility. The security barriers around Christmas markets are, in this sense, the visible consequence of an invisible cultural retreat.

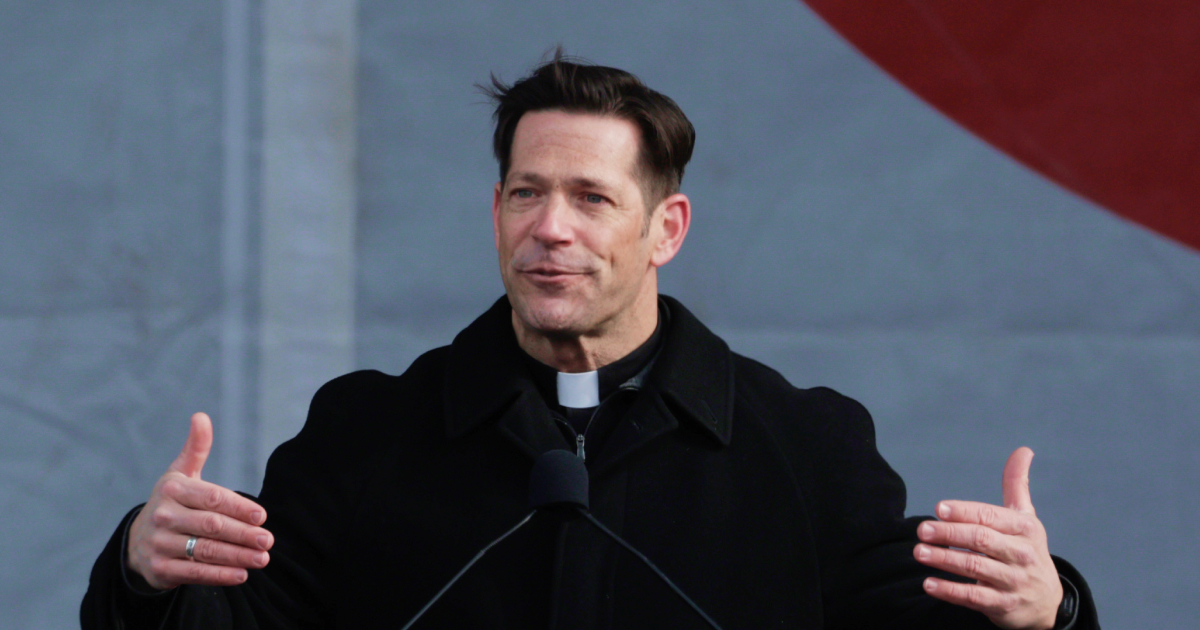

From a Christian perspective, the situation presents a dual responsibility. Nations have a legitimate right to regulate their borders, but this right must always be exercised with respect for human dignity. Pope Leo XIII affirmed that states may decide who enters, yet insisted that no policy should treat migrants in an inhuman or degrading way. These principles are not opposed; they depend on a society confident in its moral and spiritual foundations.

Europe’s challenge is that this confidence has thinned. A civilisation unsure of its own Christian soul cannot offer newcomers meaningful integration, nor can it sustain the generosity that true hospitality requires. The loss of cultural coherence does not produce harmony; it produces vulnerability.

The reinforced barriers that now shape Germany’s Christmas markets are therefore more than protective infrastructure. They are symbols of a continent wrestling with disordered migration systems, cultural self-doubt and the fading memory of the faith that once united it. The violence that shadows Christian festivals today is not only the work of isolated individuals but a reflection of a deeper crisis: Europe’s diminishing confidence in the traditions that formed it.