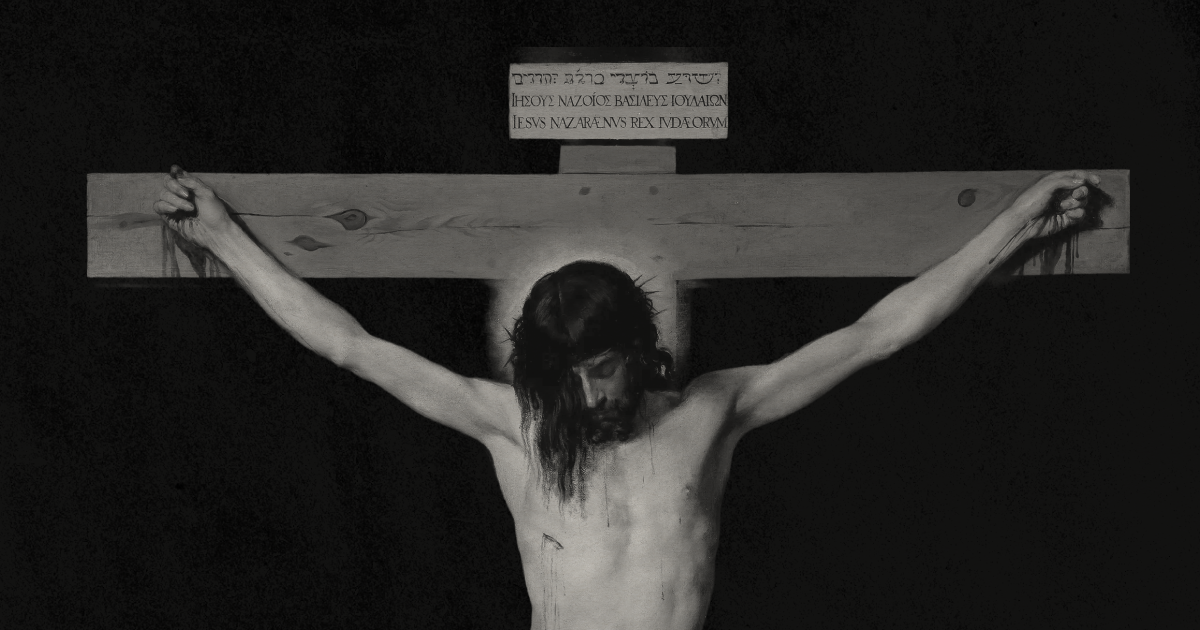

Here is a dark room in Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow, in which hangs one of the most remarkable 20th-century depictions of the Crucifixion. Painted in 1951, Christ of St John of the Cross sees Salvador Dalí jettison his surrealism in favour of Renaissance methods to depict Christ, hanging —no nails, no thorns — merely the Cross, the Saviour, and the world.

The painting is notable for the impact it has on those who go to see it. It is valued at over £60 million, but the primary threat to the painting is not thieves but assault — it has been attacked twice. Viewers who see it often report peculiar psychological effects. Regardless of what brings you there, regardless of your outlook, or the lens through which you arrive at it, it seems that meditating on the Cross brings something profound out of us.

The academic Martin Liebscher opens this new translation of the psychiatrist Carl Jung's 1939–40 lectures on Ignatius with reference to another vision of the Crucifixion — that of Jung's comments in 1957 about a vision he'd had of Christ. Jung is "scared to death" by the vision, but equally engrossed by it, turning to the Anima Christi prayer. This new edition opens with a useful contextual section regarding Jung's feelings towards the Church and Jesuits in particular, alongside helpful historical points about Jung's life and practice, which conveys a lot of information without feeling stuffy.

Moreover, while these are lectures, and as such are occasionally in a relatively technical register, they are not too demanding. Jung is conversational at times, at others more authoritative, but generally those with an interest in either Jung's psychoanalysis or Ignatian spirituality should find them interesting to read and easy to follow.

The lectures themselves are incredibly compelling. Jung spends a great deal of time bringing together three areas: the meditative practices of the East that captured the

Western imagination in the mid-20th century; his theories of psychoanalysis; and the psychological dimensions of Ignatius' Exercises.

There is much to take from this approach — the parallel between Jung's theories of active imagination and the Ignatian practice

of imaginative contemplation is fascinating, and an observation that seems obvious after the fact. Likewise, the contrast between the internal and external divisions in Buddhist spiritual practice and that of the Exercises is a profitable one, serving to shed light on the psychological underpinnings of both traditions and adding depth. The approach taken is both intellectually rigorous and spiritually provocative, and I enjoyed it.

I have spent much of my adult life engaging with the Exercises. For my money, they are the most important work of religious writing since the Gospels. I also consider Ignatius to be a great psychological thinker, and while I consider Jung's treatment of the Exercises to be useful and relatively grounded in the profundity of the call to encounter and mission inherent in Ignatian practice, I entered into this book with some trepidation.

After all, Jung's outlook is, unsurprisingly, secular: his categories don't map onto the Catholic concepts that underpin the Exercises, and I am always concerned that such

approaches run the risk of stripping out the value that exercitants find in Ignatius' work, flattening profound spiritual practice into a sort of vague therapeutic moralism — or worse, into the realm of pure individual experience.

This may well be true. But as I considered the value of such an approach, I found myself considering the importance of focus, of the need for sustained and deep engagement with stillness, meaning, and purpose.

One of the things I have thought most about since becoming Children's Commissioner is the impact of screens on children. From exposure to pornography to 12-hour screentime, I worry almost constantly about what screens are doing to children — and, let's face it, to us. The American writer David Foster Wallace spoke about the need for "some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just going to get better. And it's going to get easier and easier and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone, with images on a screen, given to us by people who do not love us but want our money."

Perhaps it does not matter from what angle one approaches the Exercises. Our modern world is loud and fast and hard; it promises individual choice and freedom while chipping away at so much of the intrinsic beauty of what makes us human — an endless sea of choice, and precious little time or importance granted to purpose.

If psychological impact is what brings a new swathe of readers to the benefits of Ignatian spirituality, so be it. It may well be the internal machinery we need to move away from isolation with images on a screen towards private stillness that opens us to oneness with something greater.

.jpg)