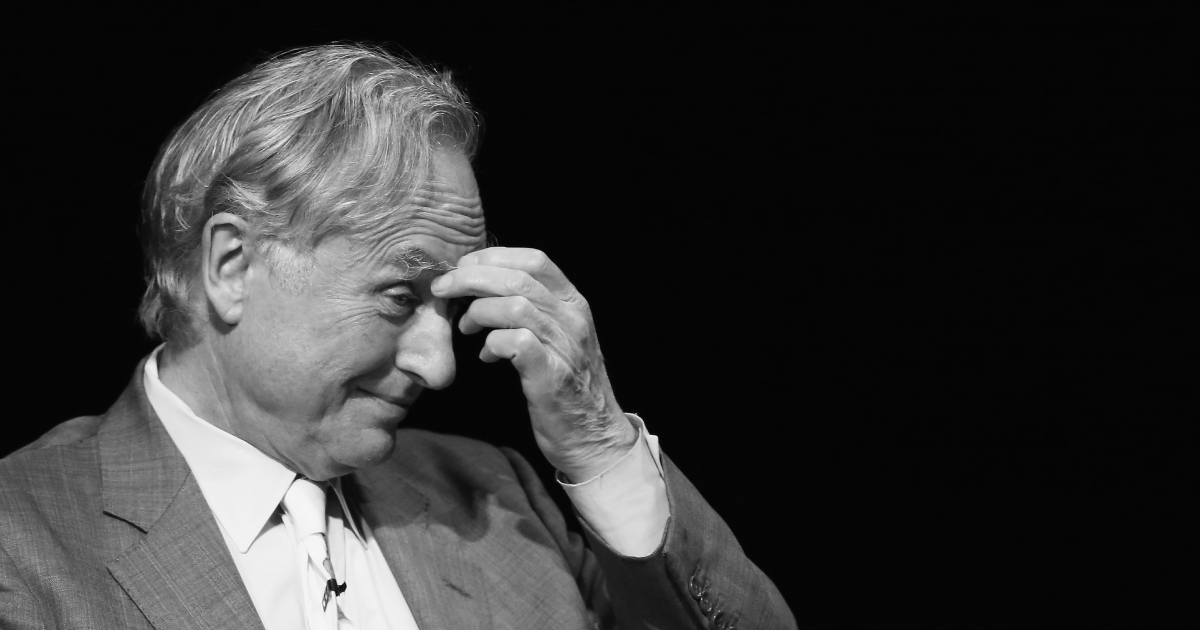

In 2006, perhaps the most famous shot was fired at religious belief. Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist and then a fellow of New College, Oxford, released The God Delusion, a 406 page repudiation of belief in a personal God, calling such belief a delusion. In the same year, the cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett released Breaking the Spell, an analysis of religion based on empirical evidence, not so much a shot but the loading of a gun for others to fire. Still in that same year, the neuroscientist Sam Harris released Letter to a Christian Nation, an open letter to Christians in the United States with the stated aim “to demolish the intellectual and moral pretensions of Christianity in its most committed forms”. A year later, the journalist Christopher Hitchens argued in God Is Not Great that religion is “violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism, tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children”.

The books were the crescendo of the endeavours of a group sometimes labelled the “Four Horsemen”, Dawkins, Dennett, Harris and Hitchens, four men hell bent on removing religious influence from public life. Circled by more intelligentsia, such as the physicist Victor J. Stenger, the biologist PZ Myers and the actor Stephen Fry, they were a thorn in the flesh of religiously minded people across the West.

The attacks were brutal and the Catholic Church was the main recipient, with a particular distaste for the Church of John Paul II, conservative, outspoken and dynamic in the developing world. Hitchens produced a documentary to discredit the work of Saint Mother Teresa of Calcutta, relying heavily on a personal dislike for the deceased Malcolm Muggeridge, but apparently not actually visiting any of her missions. He also littered God Is Not Great with attacks against the recently deceased John Paul II. Dawkins took on the late Cardinal Pell in a televised debate, particularly challenging him on the Catholic belief in the Eucharist. Stephen Fry debated the Nigerian Archbishop John Onaiyekan, lecturing him about the realities of life in Africa from a hall in London, with his justification for his patronising comments being “Uganda is one of the countries I love most in the world”. It felt that Catholicism was an obvious and favoured target.

However, almost two decades on from the release of The God Delusion, New Atheism is no longer the threat to Christendom it once was. There are several reasons for this. The first is that atheism is a dying faith. Pew Research put the number of the religiously unaffiliated as making up 16.4 per cent of the global population in 2010. By 2060, that figure is expected to fall to 13.2 per cent. Low fertility rates among those without religion, combined with massive growth in religious belief in the global South, have created a climate in which the position is less prominent than many would expect.

The second reason is that the cultural landscape of 2006 is markedly different. In 2006, in Richard Dawkins’ native Britain, 3 per cent of the population was Muslim. By 2026, that figure had more than doubled. In 2006, in the United States, 0.39 per cent of people identified as transgender. By 2026, that figure among teenagers had reached 3.3 per cent. Alongside these rapid cultural changes, a growing political unease has stirred, making criticism of what could be described as protected societal changes unacceptable. To question the social change that mass immigration from Islamic countries has had in the UK leads to accusations of Islamophobia. Concerns about children being coerced into taking puberty blockers are deemed transphobic. In turn, this social stigmatisation of dissenting views has been incorporated into the judicial process. In 2025, a 47 year old British blogger named Pete North was arrested at his home in Yorkshire after posting a meme on X, an image that included the text “F--- Hamas” along with other language referencing Palestine and Islam. Far from an isolated incident, 2023 saw UK police arrest over 12,000 people for social media posts.

New Atheism was founded on the premise that everything we believe should be tested and held to account. In 2006, it found Catholicism an obvious target, with its truth claims which, while grounded in the world’s greatest philosophical traditions, ultimately rely on faith and a personal encounter with a metaphysical Being. The early 2000s also represented a time when the evils inflicted by members of the Catholic priesthood were publicised across international media. The 2002 Boston Globe investigation and the Irish Child Abuse Commission report in 2009, as well as others, were watershed moments in the credibility of the Catholic faith.

However, twenty years later, the Catholic faith, with its Platonic, Aristotelian and Thomistic tradition, and its significant efforts to tackle child abuse within its ranks, no longer seems like the obvious target.

Now, New Atheism, faced with the lunacy of the left, proposes the same question it once posed to the Catholic faith: what does the evidence say? When faced with the question of whether radical Islam is a threat to world peace, the question is not evaded but answered in the affirmative. When one might apparently reasonably muse whether a man can become pregnant, the answer is a clear no. Suddenly, Catholicism does not seem quite so ridiculous.

This softening of views among the New Atheists has been particularly apparent in the attitudes of its leaders. Richard Dawkins, who now describes himself as a cultural Christian, told listeners on LBC that he believes “Christianity is a fundamentally decent religion, whereas Islam is not”. He has also expressed a sincere hope that the cathedrals and music of Christianity are preserved, and that with regard to Islam or Christianity in Africa, “I’m on team Christian”. Even more strikingly, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, one of the early proponents of New Atheism, has become not merely a cultural Christian, but an actual Christian.

In their second round of attack, New Atheists seem to have lost the battle, or at least become so irrelevant that few are aware they are still fighting. A generation on, there are few taking up the mantle. Two of the Four Horsemen have died, and there are no new God Delusions being published. Indeed, in Sam Harris’s latest book, Making Sense: Conversations on Consciousness, Morality, and the Future of Humanity, he chooses a born again Christian, Glenn Loury, as one of the people to help him make sense.

Ultimately, 20 years on from the God Delusion, it should not be surprising that New Atheism was unable to triumph in its mission to refute Christianity. It had a two thousand year old philosophical tradition to contend with, one with far more empirical weight than they might have thought. What may be surprising, however, is that the book's author is now “team Christian”.