On Tuesday, the world was treated to TLC’s latest instalment of Amish-related television, Suddenly Amish. In a refreshing turn from the Breaking Amish franchise, the show seems to show authentic Amish people who have lived their lives in the community. The premise of the programme is to take six non-Amish, or “English” as the Amish describe everyone who is not part of their Anabaptist faith, and introduce them into their way of life.

The six participants, Matt, Kendra, Aaron, Judah, Esmerelda and Billie Jo, all have their reasons for wanting to embrace the Amish lifestyle. Matt is a recently divorced father looking for a spiritual reset. Kendra, a dancer and content creator who has previously performed on OnlyFans, was recently baptised and is searching for “something more”. Judah, a 22-year-old rapper, feels called by God to live a more off-grid lifestyle. Esmerelda, from a Hispanic background, wants to embrace the traditional gender roles and way of life found in Amish communities. Aaron, the son of a pastor, is seeking understanding with the Amish. Billie Jo is an Amish-phile who already dresses Amish and tries to incorporate their ways of life into her own.

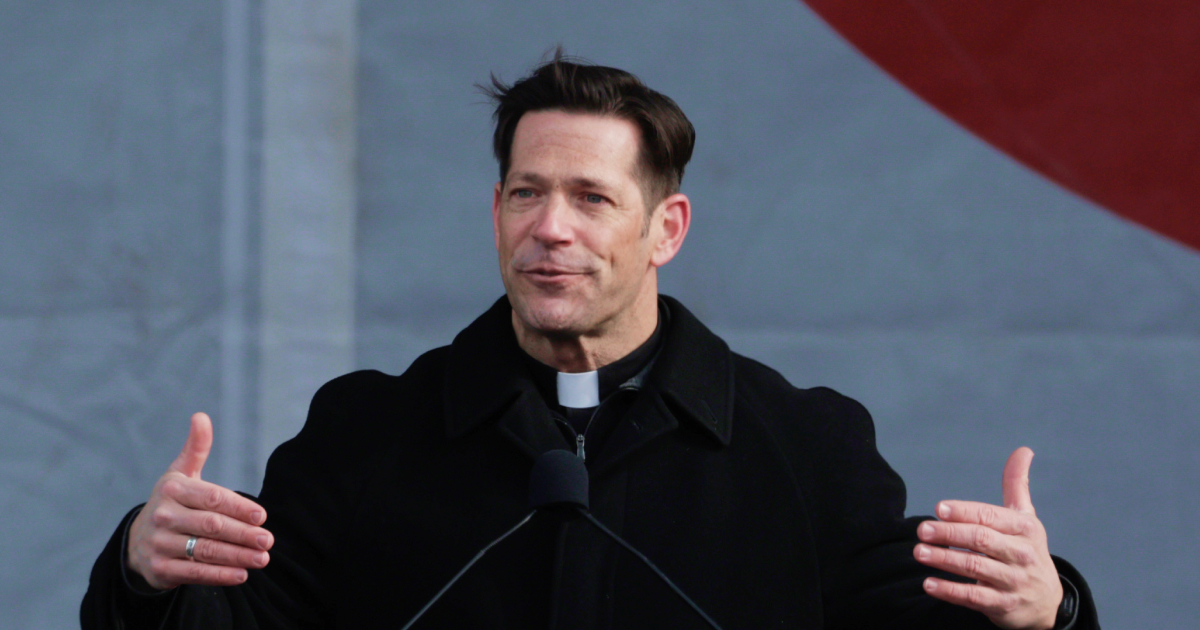

They are met by Amish Bishop Vernon, who believes God has chosen “the six outsiders” to join his community and that he has been chosen to help them do so. He does this under the pretext that many are leaving his community and that those who remain are mostly related. As a result, he believes they need to increase their fold by introducing outsiders. He enlists the help of a rebellious Amish man called James, who has been shunned from a different community, to assist with integrating the outsiders. James does so in the hope that it will lead to his own eventual incorporation into Bishop Vernon’s fold.

The six are given a month before a “day of reckoning”, when the bishop will decide whether they have what it takes to be Amish. Although only the first episode has been released, a heated disagreement with one participant over her fake eyelashes suggests that confrontation between the English and the Amish community is likely.

While the programme’s premise is that Amish communities are shrinking, this appears to be a localised issue. There are over six hundred Amish communities across the United States, and their practices and rules differ significantly. They exist as separate, self-governing communities, with both more conservative and more liberal expressions of the faith. It appears that Bishop Vernon’s community, which is more liberal, is dwindling, a characteristic shared by liberal Churches worldwide.

Across the religion as a whole, however, growth is staggering. Most Amish trace their ancestry to a few hundred immigrants who arrived from Europe, mainly Switzerland and parts of Germany, in the eighteenth century. Today, their population exceeds 375,000, with a growth rate that doubles roughly every 25 years. The average Amish woman has 6.7 children, compared to the U.S. average of 1.66. This has led some Americans to wonder how long it would take for the Amish population to match that of the United States. At current growth rates, it would take around 215 years.

They are also increasingly well placed to exert political influence. Among the six states with the highest Amish populations, three were key swing states in the last election: Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan. Amish communities are also becoming more likely to vote, galvanised by single issues such as freedom of religious education. As their population rises, it may only be a matter of time before a path to the White House requires winning Amish support.

Beyond fertility rates, Bishop Vernon’s fear that the Amish may soon disappear is unfounded for another reason: their relationship with technology is deeply appealing. It is a misconception of Amish theology that they are frozen in a particular era. Each Amish community is autonomous and therefore maintains its own relationship with technology, governed by its Ordnung, a set of unwritten rules guiding daily life. When assessing new technology, Amish communities ask whether it weakens family or community life, encourages pride, speed or individualism, or reduces dependence on the community. Technology is judged on its merits, and much of it is found wanting.

When presented with the internet, let alone artificial intelligence, which can sever community dependence and open the door to harms such as pornography, the Amish are easily persuaded that such technologies are not conducive to their service of God or their relationship with one another.

By contrast, the world outside Amish communities tends to adopt technology first and ask questions later. Artificial intelligence is undoubtedly a powerful tool for productivity, but its benefit to humanity as a whole is often treated as a secondary concern. Alienation, the promotion of pornography and the potentially catastrophic effects on the workforce are frequently set aside in the pursuit of technological advancement and financial gain for already extraordinarily wealthy individuals.

The Amish way of life presents an appealing alternative to those weary of modernity, and there are many weary souls. Research released last year by the company Moodle showed that 83 per cent of 25 to 34-year-olds in the United States reported some level of burnout. Whether real or perceived, it is clear that many people feel overburdened by modern living. Screens, long and isolated working hours, and dopamine-driven social media portrayals of life contribute to dissatisfaction with lived reality. This sense of disquiet is likely to intensify as the technological revolution continues.

From a Catholic standpoint, their approach to technology is entirely right. It should be a tool for human fulfilment and not impede a relationship with the Divine. In 2018, when presented with the staggering fertility rates of the Amish, a McGill University expert on demography and fertility asked the question: how long until we are all Amish? Eight years later, one might reasonably ask the same question without factoring in fertility at all. How long until we realise that the Amish, in their assessment of technology, have got so much right.