By their fruits you shall know them (Mt 7:16). It was the hope of the council fathers, led by Pope John XXIII, that the Second Vatican Council would herald a “new Pentecost”. That has not happened. Sixty years on, it is time to consider why, and to look seriously at what has unfolded before our eyes.

One enormous change that took place was in the everyday language and tone the Church’s clerical representatives frequently use. This is not to paint all priests and religious with the same brush, which would be deeply unfair, but when one reads or listens to homilies and writings from before Vatican II compared to after, there is a marked difference. A note can be found repeatedly present in virtually all things called “Catholic” before, which suddenly, inexplicably, fades into hushed, trailing echoes afterwards: gravity.

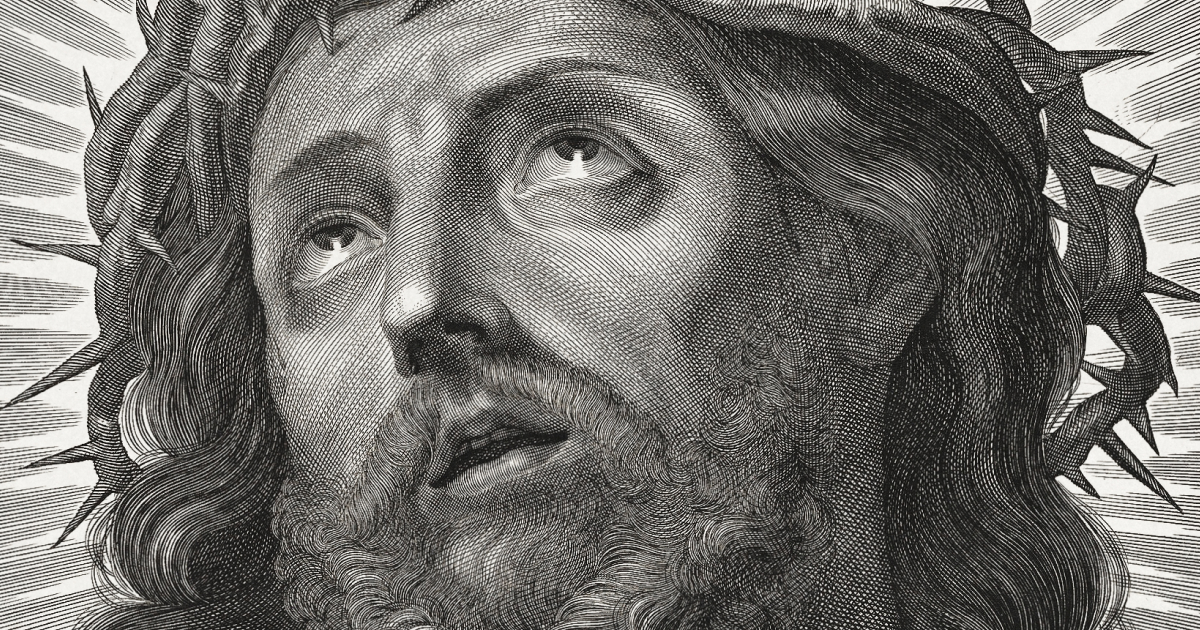

Catholicism used to be known as a serious religion. Militaryesque priests in cassocks, solemn chant, confessions heard and last rites administered to the dying with urgency. Our religion was iconically unwavering on matters such as contraception, marriage, abortion, funeral rites and, above all, salvation.

The beautifully haunting words and sounds of the Dies Irae once prescribed for all funeral Requiem Masses, now largely absent, used to be synonymous with Catholicism: a keen sense of the time the world will dissolve in ashes, the entry of the King “of fearsome majesty”, everything hidden exposed and revealed, weeping over sins, man seeking clemency from the “reckoning” of the Juste Judex ultionis, the just Judge of vengeance.

Worthless are my prayers and sighing,

Yet, good Lord, in grace complying,

Rescue me from fires undying.

This is a tone almost unrecognisable in the contemporary Church. Cartoon mascots, Michael Bublé concerts, and a great deal of time spent on somewhat vague utopian ideals like human fraternity and social justice. The Four Last Things, once a primary focus of Catholic spirituality — Death, Judgement, Heaven and Hell — have fallen by the wayside.

Before the liturgical reform following Vatican II, Catholics would yearly “beseech” Bishop Nicholas, by whose “merits and prayers” they hoped to be “delivered from the flames of hell”. In the Novus Ordo, speaking about hell was deemed too much of a downer. The Collect was amended to a more agreeable appeal that “the way of salvation may lie open before us”.

Alongside countless examples, the new Lectionary, the Order of Mass and the Breviary were deliberately stripped of numerous references, prayers and scriptural passages that treat sin, salvation and judgement with serious language.

“The reality of divine judgement. Our need for grace. Our need to repent. These are theological themes,” English academic Joseph Shaw says in the Mass of the Ages films, “and they have been removed, almost all of them.”

The shift in tone owes much to the Nouvelle Théologie, a twentieth-century school of theologians whose ideas decisively shaped Vatican II. Many of the movement’s most prominent scholars either rose to, or significantly influenced, the highest levels of the Church.

Edward Schillebeeckx, who denied the literal and fleshly resurrection of Jesus Christ, served as a theological adviser to the Dutch bishops at Vatican II. Karl Rahner was appointed peritus to the Council. Afterwards, the ideas of Hans Urs von Balthasar and Henri de Lubac decisively influenced Pope John Paul II. Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, was himself associated with the Nouvelle Théologie before becoming a bishop.

Though these thinkers differed on much, one common theme was a reluctance to use negative language about the Faith. Talk about salvation, not condemnation; healing and forgiveness, not death and estrangement; confidence in God, not wariness of the devil. Anyone who has attended Mass in the last decade and travelled around to different parishes may recognise this tone, now ubiquitous in the Church.

Having influenced the Council, the liturgy and even popes, the Nouvelle attitude soon filled seminary syllabuses. As a result, much of today’s clergy preach in their voice.

To give this flesh and bones: I once heard a university chaplain, in a very post-conciliar homily, reflect upon sin by saying, “it’s really something which makes us less alive”. That is absolutely correct and entirely valid, even helpful. But the problem was that he stopped there. The church full of young students was left in the dark about the other, equally important, side of the coin.

The Catechism of Pius X puts matters less rosily:

“Mortal sin deprives the soul of grace and of the friendship of God;… makes it lose Heaven;… deprives it of merits already acquired, and renders it incapable of acquiring new merits;… makes it the slave of the devil;… makes it deserve hell as well as the chastisements of this life.”

While the Nouvelle Théologiens were right to argue that greater emphasis should be placed on the positive aspects of the Faith, there remains a problem. Jesus, Saint Paul and Saint Peter all speak about hell and the more menacing aspects of the Faith frequently.

The Church sets forty days of penance, emulating Our Lord in the desert, for Lent, but celebrates Easter for fifty days. In the new spirituality, when all year is Easter and little time is spent in the desert, repentance and confronting darkness are reduced to a minimum. Easter itself loses some of its power. The light shines less brightly when we are not conscious of the darkness it dispels.

It is now not uncommon to find priests who preach as though salvation is guaranteed and inevitable, hell a distant memory and absolution merely an option. Catholics cannot lose sight of the fact that we, as sheep, need direction from our shepherds, and when we do not receive this adequately it has an all-too-real, tangible and often catastrophic impact on countless souls.

Related to this, a frightening phenomenon few wish to talk about has emerged: the catastrophic disproportion between the number of souls making frequent confessions and the number of souls receiving Holy Communion.

It is an ancient and scriptural teaching that those who receive the Eucharist unworthily, in a state of mortal sin, are “guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord” and eat and drink their own condemnation.

Yet today, in Masses around the world, entire congregations go up to receive the Eucharist. Hundreds at a time. But ask the priests how many use the confessional, and the numbers do not add up.

Catholics may not be aware, but for generations of our ancestors, receiving Holy Communion was a very rare and grave occurrence. Daily Mass attendance was frequent – farmers would refuse to set hand to plough without first setting their eyes upon their Lord in an act of solemn worship, as the late scholar Fr John Hunwicke warmly recounts. But Catholics were so conscious of the awful holiness (and dangers of profaning) the Eucharist that the Church had to compel them to receive it at least once a year. As the Synod of Elvira confirms about the early Church, it was not uncommon that certain sins could deny you the Eucharist for years – even for life.

Nothing like the laissez-faire, carefree approach to this most sacred host, ubiquitous today, has a history in the Catholic religion. It was firmly known that our approach to the Eucharist is one of the most serious moments in all our mortal existence, that we must examine ourselves beforehand, be repentant and purified, and that heaven, hell and eternal life were on the line.

And to spare any trad-Wahhabi hysterics: frequent Communion was a gradual development in the Church and no modernist plot. St Pius X – hammer of modernists – flung open the doors, provided Confession was used and mortal sin avoided.

Perhaps this was sensible. The medieval peasant, surrounded by silence, sacraments, greater harmony with nature and the rhythm of the Church’s year, may have needed the Fortifying Salve only once a year. Modern man, relentlessly assaulted by screens, advertisements and billboards, harried by a thousand invitations to vice before breakfast, needs it far more often.

Fear and seriousness are not all there is to the Faith. Lightness and humour matter too. St Philip Neri famously shaved half his beard to look absurd and amuse his flock. But there are moments when frivolity must be set aside, especially when confronting the Four Last Things.

Dr Peter Kwasniewski has said: “the holy fear of God, which begins in the dreading of His just punishments for sin… matures into love of Him for His own sake and a desire to dwell with Him forever in heaven”. And Scripture reminds us: There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear (1 Jn 4:18).

The salvation of souls is the supreme law of the Church. Do her servants today remember? Perhaps it is time the Nouvelle should cease overriding the old theology, and the sensibilities of Pius X and the Dies Irae return.

When shepherds no longer speak and act as though eternity is at stake, eternity ceases, for many sheep, to feel as though it is. That is a fruit of the Council few foresaw – and one the Church can no longer afford to ignore.