Brought up amidst much turmoil – his father and three regents murdered; his mother deposed when he was an infant and subsequently judicially murdered by her and his cousin – James VI somehow survived into adulthood as an “intelligent, resilient, idiosyncratic, guileful and witty” man, in the words of a new biography of him, The Mirror of Great Britain: A life of James VI and I, by Clare Jackson.

Readers of this periodical, however, are most likely to want to know about his attitude to Catholicism. But before we get to that, his was an adventurous life, though he died in his bed (only the second of the seven Stuarts to do so). He was the first ever King of Great Britain (and indeed King of Ireland too). With Europe riven by wars of religion, he was more successful than anyone else between 1541 and 1746 in holding the peace both at home and abroad.

As an adult, he survived attempts at kidnap and assassination – "Remember, remember the fifth of November" – but unlike his mother, his cousin Elizabeth or his son Charles, he faced no rebellions or civil wars, he avoided foreign wars and he attempted to bring peace between warring nations and faiths abroad with limited but not negligible success.

He was a king for 57 years, having been crowned aged 18 months. He ruled for 40 years, second only to Elizabeth amongst the Tudors and the Stuarts. And yet, he is the least well known and absolutely the least understood of all of them. His stock has been rising for the past generation and the much-lamented Jenny Wormald laid the foundations of a proper understanding but did not live to finish her biography.

We have to make do with essays and a wonderful impish life in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Alexander Courtney has now published the first of two volumes of what looks set to be a definitive life told chronologically (James VI, Britannic Prince, Routledge, now in paperback). I mention these because while we should applaud Clare Jackson’s new biography of the man who was James VI and James I, and especially her very imaginative construction of a biography written thematically rather than chronologically, it will not be a straightforward read for those unfamiliar with the timelines (he was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until his death in 1625).

Although themes are introduced in a way that leads from early life to later life, most chapters cover long periods and there are gaps. For those with a grasp of the narrative from general histories and previous lives, this matters not. For what each chapter gives us is a vivid, deeply informed and persuasive account of how he came to be the man he was: to Clare Jackson’s “intelligent, resilient, idiosyncratic, guileful and witty” we can add (as she has also demonstrated) “learned, overconfident, gauche, flawed”.

He strove with more success than frailty to be a renaissance man. Clare Jackson’s first substantive chapter is entitled “A King of Words”, as he was the most published, the most polished, the most proficient writer of poetry, prose, biblical commentary of any ruler in Renaissance Europe. He was very ruthlessly educated and although he came to reject the ascetic Protestantism of his tutors, he retained their commitment to Christian humanism and the spirit of enquiry.

Jackson uses his writings – on politics, religions, poetry, witchcraft, the perils of tobacco and on and on – to give us the man (she also details his contribution to European debates, his engagement with lawyers on the benefits of roman law over common law and the relish he took lecturing clerics on theology and ecclesiology). This engagement with the range of his writings is cumulatively what makes this such a rounded and persuasive portrait.

Several of the chapters, such as the one on James’s obsession with hunting (and not only with the chase but with the kill), a chapter attractively and punningly entitled “The reins of government”, and the one on his less intense but utterly persistent concern with witches and diabolism, are not only very interesting in themselves but revealing about the inner man, otherwise deeply camouflaged.

Regarding his attitude to Catholicism, the answer, Clare Jackson demonstrates, is ambiguous. He was a baptised Catholic, of course, with a furtively Catholic convert wife. He told a shocked Parliament in 1604 that he recognised “the Roman Church to be our Mother Church although defiled with some infirmities and corruptions”.

But the handsome table clock made for him in Dundee had on its sides images of the four Evangelists, but hidden on its base an engraving of James and his sons holding the Pope’s nose to a grindstone (this is the twelfth of the 28 beautifully produced plates that adorn the book).

At home, James preached tolerance but not toleration, as well as not repealing the bloody penal code enacted by Elizabeth, but enforcing it far more laxly. In Scotland he sought to bring the Catholic peers into the court and government rather than persecute them. There was less of that in England, and even after the Gunpowder Plot there was no over-reaction once those immediately responsible had been tortured to death.

And internationally he actively pursued the plans of others for ecumenical councils that might still heal the schism, and from the 1580s he always had open channels of communication and warm words for successive popes. All this is very well captured. If there is a disappointment about the book, it is the lack of depth in its coverage of James’s policies in Ireland. There was a lot less slaughter there than in the period 1570-1604 (let alone 1641-60 or later), but less accommodation too.

Still, let’s end on a high. This is a wonderful read, a very clever book both in structure and argument, and at last we have a book that recognises the last great humanist ruler with high ideals and a good deal of pragmatism.

If his vision of a perfect union of kingdoms, as well as of crowns, was wrecked by the small-minded xenophobia of his English subjects, they and we were the losers. This is the biography he has long deserved.

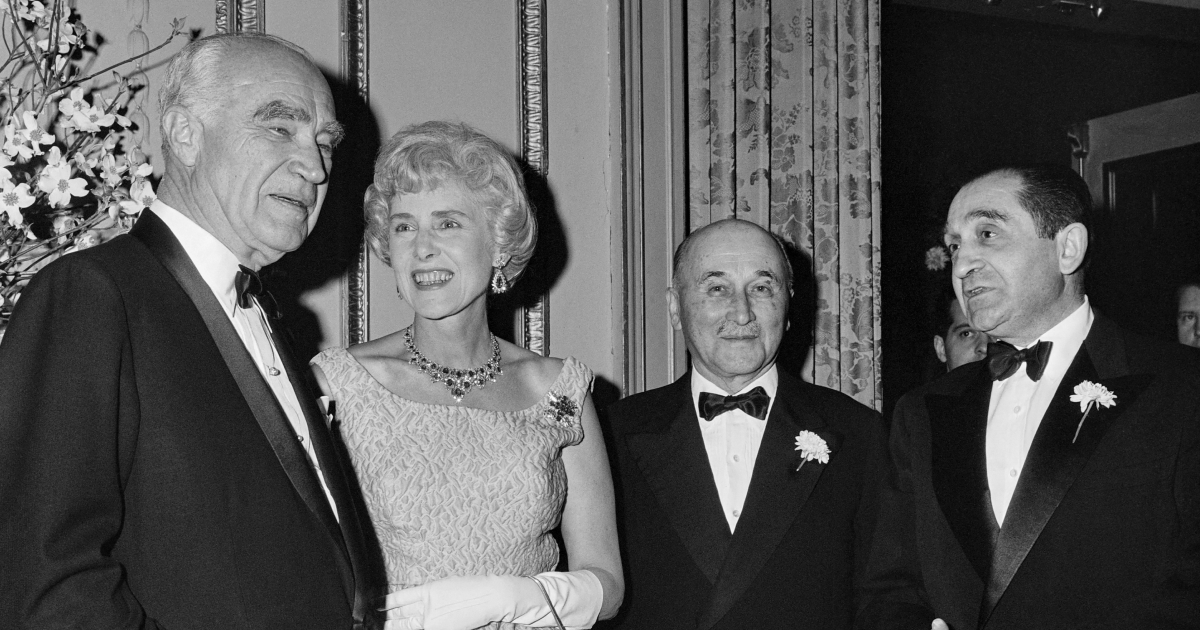

Photo: Portrait of King James VI and I attributed to John de Critz, c. 1605. (Wikipedia/Creative Commons.)

Fr John Morrill, in addition to being a Catholic priest, is a sometime Professor of British and Irish History in Cambridge.

The Mirror of Great Britain: A life of James VI and I by Clare Jackson, Allen Lane Imprint, 530pp, £35.