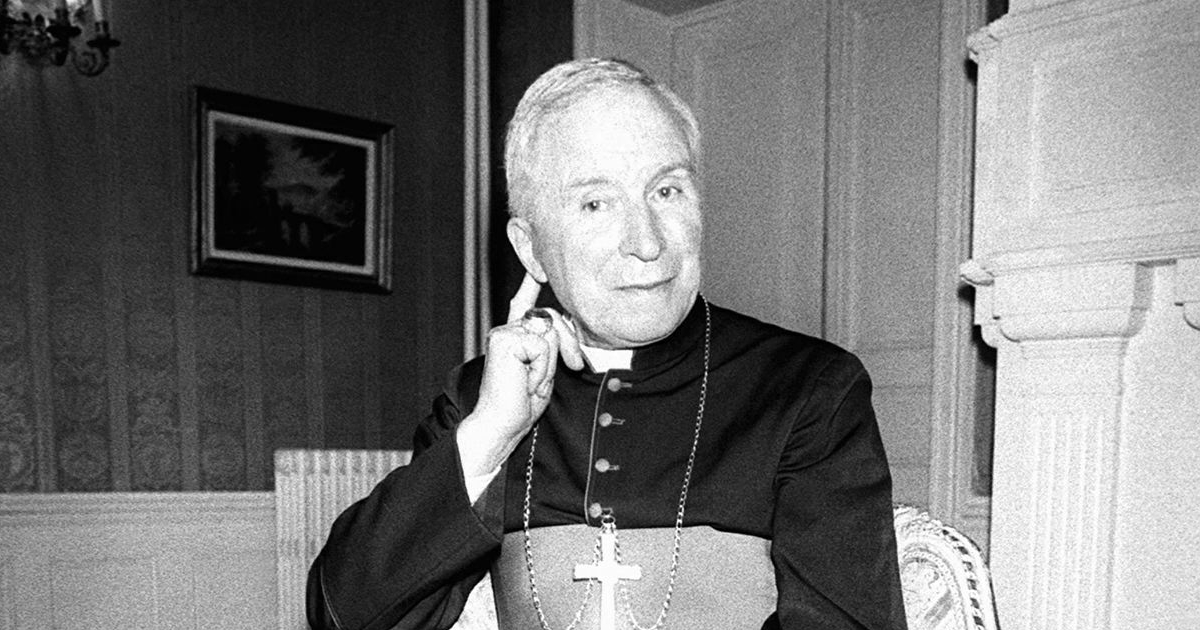

Henry Edward Manning’s engagement with social issues is well known. His work in favour of the Jewish people, on the other hand, has not received the same attention.

Manning’s contact with the London poor and his awareness of their needs led him to admire Jewish concern for the disadvantaged in their own community. Indeed, he held it as an example for Catholics to imitate. It was not, however, until the early 1880s that he became directly involved in Jewish issues, on the occasion of the Russian pogroms of 1881-82 and the British appeal to the tsar in favour of the Jews.

Towards the end of the 18th century and at the beginning of the 19th, Russia had considerably expanded her frontiers westwards between the Baltic and the Black Sea, absorbing within her borders large parts of what are now Lithuania, Belarus Poland and Ukraine. In so doing Russia annexed territories in which Jews made up between 12 and 18 per cent of the population. The Jewish Pale of Settlement, established at the end of the 18th century in the territories mentioned, restricted the Jewish people’s right of permanent residence and of work outside the Pale, and limited their right to buy and farm land.

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in March, 1881, marked a worsening in the situation of Russian Jews. One of those implicated in the murder was of Jewish origin and rumour added other Jews to the plot. This provided the occasion, or pretext, for anti-Jewish riots, particularly in the southern part of the Pale of Settlement.

The Board of Deputies and the Anglo-Jewish Alliance felt called upon to intervene in support of their Russian brethren. The sergeant-at-law and MP John Simon briefed the cardinal about the sufferings of Russian Jews and asked him to support the call for a public meeting to address the issue. That meeting took place on February 1, 1882, in the Egyptian Hall at Mansion House. Manning proposed the second of four resolutions to be passed. It read: “That this meeting, while disclaiming any right or desire to interfere in the internal affairs of another country … feels it its duty to express its opinion that the laws of Russia relating to Jews tend to degrade them in the eyes of the Christian population, and to expose Jewish subjects to outbreaks of fanatical ignorance.”

Russian Jews, Manning added, were not allowed to pursue honourable careers in public life and were restricted to living in certain places. To loud cheers, he affirmed that the Jewish people were endowed with an inextinguishable life, having preserved their traditions and faith in God in the face of innumerable adversities. He went on to praise the Jews in France, Germany and particularly England “for uprightness, for refinement, for generosity, for charity, for all graces and virtues that adorn humanity where will be found examples brighter or more true of human excellence than in this Hebrew race.”

In an editorial the following day, the Times said that “among many admirable speeches made yesterday that of Cardinal Manning is the most remarkable”.

The meeting approved the creation of a fund to help Jews leaving Russia. Manning was appointed a committee member and took an active part in its weekly meetings, presiding at them on many occasions.

In March 1882 his attention was called to the danger that the pogroms might extend to the Polish part of the Jewish Pale. Manning wrote immediately to Rome, and British Jews attributed to his influence a letter from the pope, read from all Catholic pulpits in Poland and designed to prevent attacks on Polish Jews.

In 1889 Manning intervened once again on behalf of the Jewish people. At that time, the blood libel, the medieval accusation that Jews kidnapped Christian children and used their blood for baking the unleavened Passover bread, had been renewed in a French book. The author claimed that his book had been commended by Rome. Acting on a request by the then acting Chief Rabbi, Manning asked Rome to contradict that claim and received by return of post a letter to that effect from Cardinal Mariano Rampolla.

When Manning celebrated his silver jubilee of episcopacy in 1890, the Council of the Anglo-Jewish Association presented him with a congratulatory address. The Jewish Chronicle commented: “If the Cardinal had been Chief Rabbi he could not have acted more energetically in favour of the Jews than he did on occasion of the Russian persecution.” The address, on decorated parchment, was enclosed in a magnificent ebony cabinet. Manning was fond of showing it to visitors, pointing out that this gift represented “the one incident in my life of which I am most proud”.

The year 1890 saw a worsening of the conditions experienced by Jews in Russia. Manning once again signed a requisition asking the Lord Mayor to convene a meeting to complain on behalf of Russian Jews. It took place on December 10. Manning had hoped to address it but in the end was too weak to do so. He wrote an eloquent letter to Sir John Simon regretting the fact.

When Manning died on January 14, 1892, the presidents of the Board of Deputies and of the Anglo-Jewish Alliance sent joint condolences to the Provost and Chapter of Westminster Cathedral. “By his noble life,” they said, “and the uniform kindliness and courteousness of his manner, the lamented Cardinal earned for himself the esteem and admiration of all classes and the sincere and enduring gratitude of the Anglo-Jewish community.”

Fr James Pereiro is an Opus Dei priest