Much of the Barbican Centre seems to be below ground level, somewhat like a well-appointed bomb shelter. After getting lost in a subterranean corner of B2 called The Pit, the exhibition space of Encounters: Giacometti x Mona Hatoum is an almost Alpine world of light and altitude. Unlike the Barbican’s post-war palette of grey, with splashes of watery green, the world of Giacometti and Mona Hatoum is all about contrast — in invigorating monochrome.

Despite the huge gulf between the two artists, they have much in common. Death is all around, as is hope for peace. Both sculptors have taken a keen interest in the subject. Giacometti died young in 1966, while Hatoum is a vigorous 73 years old. Unlike the Swiss sculptor, who grew up in a notoriously peaceful and — according to Orson Welles in The Third Man — uncreative place that produced cuckoo clocks, Mona Hatoum has Palestinian roots. She also lived in Brixton at a time when it was far from the comparative serenity that now prevails there.

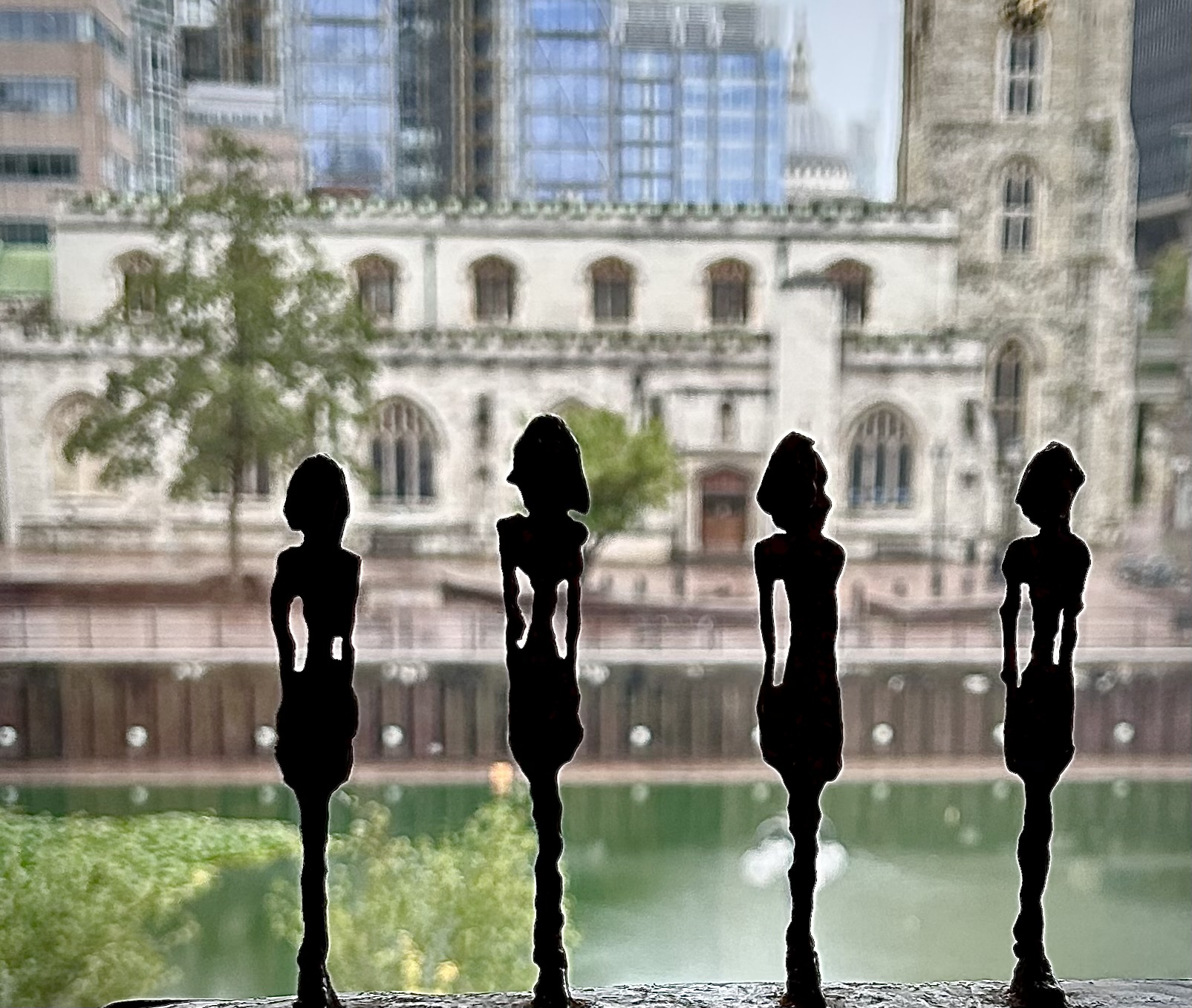

The religion of neither artist is alluded to in the exhibition. Mona was probably brought up Catholic, or at least Christian; Giacometti appears to have been part of a community of Protestants of Italian descent. Overtly spiritual elements are absent from the space. There are windows, however, and in the City of London one is never far from a church. Facing the panoramic wall of glass is St Giles’ Cripplegate. It’s one of those names that would no longer exist if it were anywhere but the Square Mile. It remains a beacon of soft-hued stone against the concrete grisaille work that is London EC2. In addition to being a rare medieval survivor in the City, it’s a venue that provides the sort of welcome the Anglican community tries so hard with. Among its many attractions is a bring-your-own-lunch Bible study day.

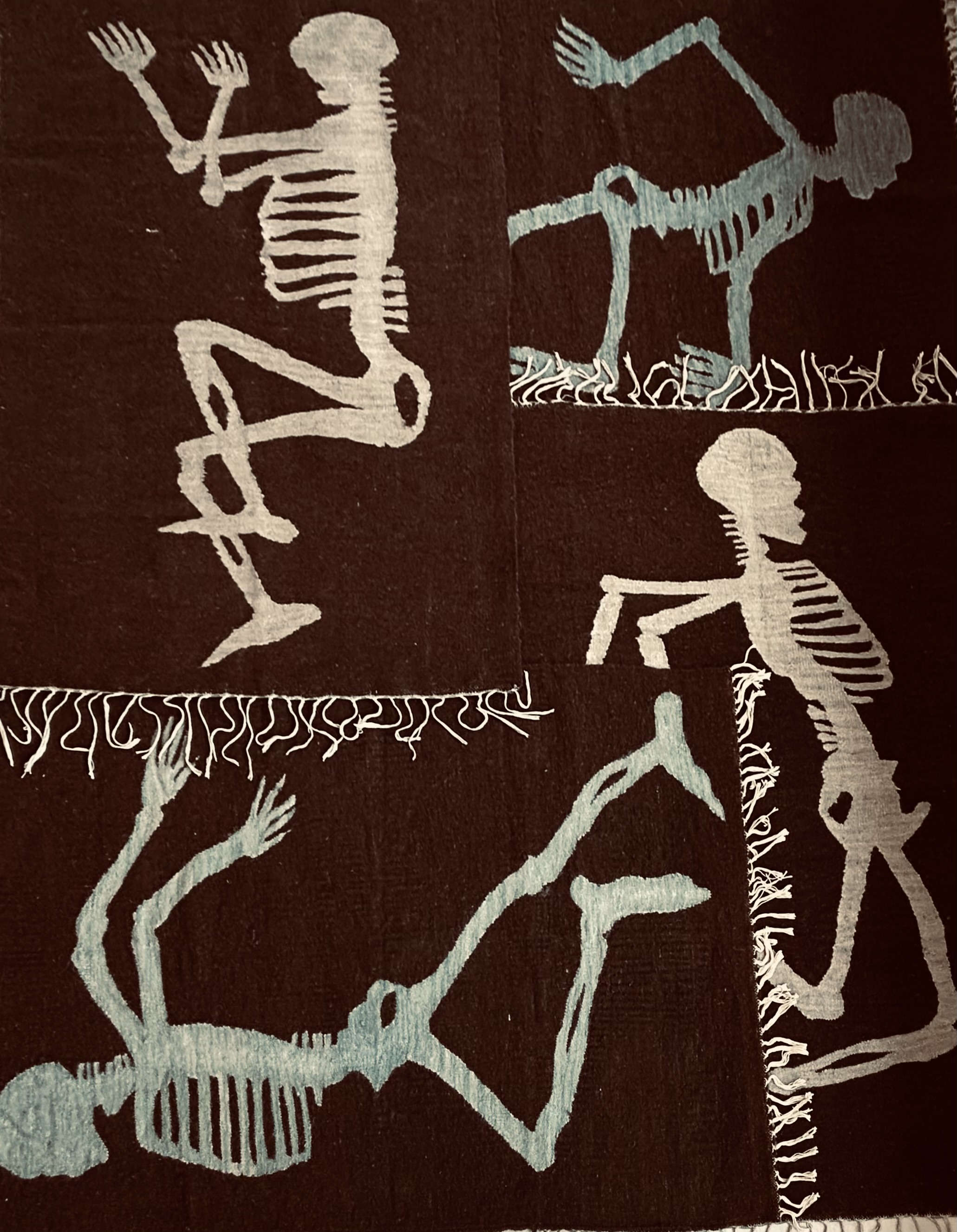

St Giles’ Cripplegate would be a pointless digression were it not for the fact that the works on display at this exhibition are more integrated than most into what lies beyond the windows. It’s not clear if that was the intention; certainly, the entire inner space is seen by Mona Hatoum as a complete installation. What a relief that it doesn’t entail anything too high concept, such as brushing past naked bodies at the Royal Academy exposition of Marina Abramović in 2023. In fact, there are no bodies at all in Hatoum’s work, unless we include the fleshless woven skeletons in a fascinating arrangement on four floor rugs. This manifestation is vaguely reminiscent of those Tantric objets d’art which take the Catholic attachment to relics into another realm.

Hatoum creates situations and settings in which the human form would be superfluous anyway. This is where Giacometti steps in. He created almost nothing except humanoid bodies, usually the etiolated type seen brooding or striding across the countless galleries in which his work has been exhibited. At the latest Barbican show, there is the bonus of a feline form. It’s a delightful rendering, prowling within the Cityscape like Dick Whittington’s companion.

The present exhibition is the halfway point of three encounters that bring Giacometti together with contemporary artists. Huma Bhabha’s collaboration happened recently, and Lynda Benglis’ turn is due in February 2026. Until then it’s Mona Hatoum, a very topical artist.

Just as Giacometti developed advanced anxiety from the destruction of the Second World War, Hatoum is stirred by more current conflagrations. Being of Palestinian descent, there is that ever-present conflict in the background. As most of her work was created long before the 7 October atrocity, it’s a useful reminder that the battles in the Holy Land have been bubbling away for longer than two years. Not that Hatoum’s focus is oppressively about the Palestinian cause. She is against all injustice, and there’s no need for trigger warnings about flags, rivers, the sea or any proscribed organisations. She is above that. As with Giacometti’s anti-war stance, there is no preaching or politicising.

It is often suggested that both artists’ work uses humour, usually preceded by the qualifier ‘dark’. It’s sometimes hard to see the wry side in the gloom, though. That requires imagination — and sometimes pretty good eyesight too. Hatoum’s famous metal cot with piano wire instead of a regular base is chilling; even more so if one recalls Hitler’s most sadistic forms of execution. The wire is so fine, you have to get close to see it at all, which doesn’t make it any less disturbing.

Everything here is designed to provoke thought and a reaction, as well as having an aesthetic dimension. The most visceral item on display is the one that greets visitors — and comes with a warning from the ticketing staff. It’s not so much ‘don’t touch the exhibits’ as ‘don’t step on them, or trip over’. The title of Giacometti’s 1932 Woman with Her Throat Cut is alarming, or would be if there were any labels nearby. In a pleasantly old-fashioned approach, there is instead a sturdy card brochure with descriptions and line drawings to indicate which hazard is which. Woman with Her Throat Cut needs it, as the first impression is of a botanical study. This is Giacometti at his most aggressive, a world away from the calm of his more famous walking figures or the possibly comical The Nose from 1947. The curators inform us that this work might be either a person screaming in agony or a lifeless corpse. I’d go for the latter, especially as Giacometti had recently witnessed two deaths in which, he reported: “The nose became more and more prominent…the almost motionless mouth barely breathed.” Either way, it’s a milestone on his migration from Surrealism to humanism.

For this exhibition, The Nose has been removed from the rudimentary cage in which Giacometti placed it. The new enclosure is something much more substantial by Mona Hatoum. Cube is a massive steel cage of medieval solidity in which The Nose is definitely not having the last laugh. The feeling of imprisonment is inescapable, and that is how the show goes on. As visitors wend their way towards the far end of the gallery, the fascination mounts. Is it going to get grisly? Fortunately, the answer is no. Dispel those nightmares of the aforementioned Marina Abramović. There are no piles of bones being scrubbed by Serbia’s most famous cultural export and exhibitionist.

Encounters is more nuanced and sometimes needs more explaining. Hatoum’s Remains of the Day (2016) has no connection with the Merchant-Ivory ode to regret. Hatoum’s version was conceived as a response to the atomic bombing of Japan but could refer to any of the conflicts that see massive firepower aimed at civilian populations. The charred remains of domestic furniture have a universal look, an Ikea fire sale rendered in wood and wire mesh. More specific is the sad little room which comprises the installation Interior Landscape (2008). This is Palestinian life, although you have to look quite hard to pick up the clues. Far more visible, opposite Hatoum’s work, is a farewell from Giacometti before the exhibition ends with several key pieces by his contemporary admirer. It’s one of those legendary elongated figures of the Swiss master sculptor, albeit on a smaller scale than usual. It’s also behind glass and placed between two boxes: more suggestions of incarceration rather than the incineration happening in Remains of the Day.

The exhibition ends with further incendiary thoughts. The final work is Hot Spot (2018), which has more colour than the whole show combined. The red neon globe suggests destruction — by climate change as well as warmongering politicians. It reflects gloriously on the gallery windows, encouraging one to look around and realise that the only thing saved from the Luftwaffe is St Giles’ Cripplegate.

Old-timers will also want to pay tribute to the recently deceased Tom Lehrer at this stage. In addition to nuclear apocalypse in the song We Will All Go Together When We Go (“All suffused with an incandescent glow”) he also mentioned the bombing of London that caused the Barbican to rise from the ashes: “Like the widows and cripples in old London town / Who owe their large pensions to Wernher von Braun.” Von Braun was hired by the USA when the Department of War was still in business. Now it’s about to return, long after Giacometti’s peace baton was passed to Hatoum. Encounters confirms that both artists have a conscience, continuity, and their fingers on the pulse of human fragility, which is so often hard to find.

.jpg)