At the age of four, Jean-Marie Charles-Roux wrote a note to Father Christmas, “Please send me toy soldiers to defend the Pope”. The wooden figures in the uniform of the Swiss Guard were still on his shelves at his death ninety five years later. Given this early mission, his later calling as a priest and his familiarity with three Popes was perhaps inevitable, but this did not prevent him from challenging them on issues he felt strongly about. As someone who believed in the Tridentine Rite, the Divine Right of Kings, that Marie-Antoinette should be declared a Martyr, and that the civilised world had vanished in 1789, Fr Charles-Roux was increasingly at odds with the modern twentieth century Church. Yet his fundamental faith, his abiding charm and courtesy, and his conformity with many respects of doctrine (even his liberality on others) helped him escape dismissal as an eccentric relic and allowed him to become a widely admired yet singular member of the Catholic Church.

Fr Charles-Roux’s thirty five years as spiritual coadjutor and preacher at St Etheldreda's at Ely Place off Holborn Circus confirmed his vocation as the saviour of princely and noble souls. As his counterpoint in almost every respect, Bishop Victor Guazzelli, whose see took in Tower Hamlets and Hackney, observed, “it is good to have priests like Fr Charles-Roux who wander around with the classy people because whatever titles they have, they still have their own problems.”

And yet, as his friend Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith noted in an affectionate tribute in the Herald, “the only ancestor who had played any role in the Revolution, he told me, was one of the guards at Versailles, who was killed during the storming of the Chateau on 5th October 1789.”

Although the Abbé’s beginnings were more modest and his circle more eclectic, Fr Charles-Roux’s fame recalled that popular figure of the Belle Epogue, Abbé Mugnier, a favourite of the Faubourg, an intimate of the old French aristocracy and a close friend of Proust’s, whose tolerance, wisdom and compassion was appreciated even by the godless.

Jean-Marie Charles-Roux was in fact a member of the Midi’s Haute Bourgeoisie. Prosperous from three generations of manufacturing soap in Marseille, the family had built a fortress like chateau nearby at Sausset les Pins and played a part in local affairs. The fourth generation, Francois Charles-Roux, became a diplomat and married Marie Virginie Sophie (Sabine) Gounelle, daughter of another wealthy Marseille merchant and the owner of the beautiful Renaissance style Villa Valmer.

Jean-Marie was born in Rome on 12 December 1914, the eldest of three children and their only son. With his English nanny, he followed his father’s postings to St Petersburg, Constantinople, Cairo, London and Czechoslovakia before Francois was appointed Ambassador to the Holy See in 1932. Jean would also follow his father’s calling as a diplomat.

Francois resigned from Vichy’s Foreign Office in 1940. Young Jean, according to Fr Lucie-Smith, escaped to England via Spain, “swimming a river in full spate in winter. The Spanish arrested this dripping and naked Frenchman, and he was imprisoned for some time.” In England he joined General de Gaulle and the Free French.

After the war, he was posted as an intelligence officer to Greece, where he often called upon the aunts of the Greek King, Princess Nicholas (mother of Princess Marina and grandmother of Princess Alexandra) and Princess Andrew (mother of Prince Philip). He told Princess Andrew’s biographer, Hugo Vickers: “Princess Nicholas was very religious and mystical. She would have gone to the stake for her religion. She had an energy and a will that Princess Andrew didn’t have. She thought Princess Andrew did not understand religion. But Princess Andrew (Alice) later founded the only order of nuns in Greece to do social work. Alice said, ‘It is all very well for Princess Nicholas forever attending the liturgy, but we must be practical.’” These formidable figures were only two of many besieged or exiled royals, from Victor-Emmanuel III of Italy to Constantine II of Greece, whose confidences he shared.

In 1950, he commenced study at Beda College in Rome. In 1954, at the age of 40, he was ordained. Jean chose the Institute of Charity, the Rosminians, perhaps because the founder, Antonio Rosmini, was a remarkably original thinker, but also because he was impressed by the Order’s seminarians he had met in Rome. His father was aghast that he would enter an Order which would not allow him to join the hierarchy as bishop or cardinal. Pius XII, no less, intervened.

For two years he taught religion at Ratcliffe College in Leicestershire. He was not a natural teacher, so easily distracted and forever dropping names yet never breaching a confidence. His compassion meant that lines to his confessional were longer than any others. After a short time at a Rosminian parish, St Peter’s in Cardiff, he spent five years at the Order’s noviciate at Wadhurst in East Sussex, from where he assisted the Apostolic Delegate.

In September 1964 he found his metier in London’s oldest Catholic Church, St Etheldreda’s, built in the reign of Edward I. Unburdened by administrative duties, he was the Assistant Priest who preached every Sunday at 11 am. His highly original homilies, lasting no less than 25 minutes, drew a devoted following. In 1976 Harpers and Queen featured him first of the Catholics in its Good Sermon Guide: “Immense presence, Palace of Versailles aura. Said to like court intrigue. Preaches good manners in a foreign accent.”

His appearance only deepened the anachronistic image. The Rosminians had introduced the Roman collar to Britain when they first arrived in 1835 and were the first Catholic priests since the Reformation to wear religious habits in public. With his slightly frayed black cassock, buckled shoes and pince nez (sometimes a monocle when he read a newspaper), Fr Charles-Roux captured the spirit of 1835.

In 1971, he had sought a personal audience with Paul VI, whom he had known as Cardinal Montini. "For 18 months I have celebrated the new Mass, but I cannot continue. I was ordained to celebrate the old Mass, and I want to return to it. Will you permit me to do so?" The Pope apparently replied, "Certainly, I never forbade celebration of the old Mass; I have only offered an alternative." Another version of the audience has Father saying, “Holy Father, if I could just celebrate the old Mass, or I leave the priesthood and marry the first pretty girl I meet.”

There was some spirited correspondence in these pages. In a letter dated 4 January 1974, he wrote, “I also fail to see why one should take with blind faith any decree emanating from the reigning Sovereign Pontiff or his immediate predecessor — both, incidentally, almost life-long personal friends of mine — and why one should not attach the same importance to all the decisions and teachings of all the other Popes.”

“Reigns in the Church, I would maintain most stubbornly, are not successive but cumulative. Hence I consider it the duty of the members of religious orders, male and female, who are the official thinkers and "beacons" of the Church, to detect the connections and warn against the discrepancies, as did St. Jerome and St. Bernard, St. Catherine and St. Theresa, John Henry Newman and Teilhard.”

Later in the same letter he wrote, in characteristic vein, “Finally, to Mary Thomas, who writes: "Who on earth is Fr. Jean Charles-Roux, author of the article 'So-Called Renewal,' in your issue of November 30? Poor Soul!" I will dare to confide that were she to participate in Mass as I offer it, that is while giving Our Lord a chance to be heard and share with us his sight, she would know me as well as I do her. Dear soul!”

But Fr Charles-Roux’s Tridentine Rite was his own. Recited, with eyes closed, in an almost ecstatic trance, it lasted never less than 90 minutes, and sometimes much longer when he remembered the dead Kings of France.

He led a passionate crusade (not just in print, Louis XVII: La Mère et l'Enfant Martyrs, but often from the pulpit) to seek martyrdom for Marie-Antoinette, “loyally following Christ as far as the cross”. Like Charles I, in forgiving her tormentors, she had a perfect Christian death. He did the same himself, immediately forgiving a young man who stabbed him, not quite fatally, one day at Ely Place.

He proposed Mary, Queen of Scots, for martyrdom and, according to the Chaplain of Keble College, he even suggested George IV should be canonised for his faithfulness to Mrs Fitzherbert.

In two books, L'Apastasie Nationale (1977) and Mon Dieu et Mon Roi (1978), he illustrated his belief that the state was a contractual nexus of families and that consecrated monarchy was an imitation of Christ the King. The ruler, as he saw it, does not choose to set himself up but is chosen by God to become a servant and govern prayerfully, lovingly and with justice. He was, unsurprisingly, a great favourite of the Legitimists. At a memorial service at St Etheldreda’s in 1989 for Prince Alfonso de Borbon (as Duke of Anjou the Spanish claimant to the French throne), beheaded by a cable at the finish line of the World Alpine Skiing Championship at Beaver Creek, Colorado, Fr Charles-Roux compared his death to that of Moses, who died before reaching the Promised Land.

In his view, Church and State should be one. He dreamt that one day the Archbishop of Westminster and the Archbishop of Canterbury would take their first Communion together at St Etheldreda’s. He would surely have been pleased to see Charles III (and Vincent, Cardinal Nichols) praying with the Pontiff in the Sistine Chapel in October this year.

In L'Apostasie Nationale, he offered, as a review of the Catholic Herald put it, “an optimistic, farsighted view of the European Community, not as a squalid, self-seeking cartel, not as the hatching-ground of another Napoleon ("ce Caliban du Corse"), but, together with the Commonwealth, as a new, pioneering supra-national society, and the Empire's heir, more peacefully, more evangelically, bringing salvation to mankind.”

His reviews for this journal in the 1970s revealed a liberal approach to Church teaching but again drew on the past. In reviewing Norman St John-Stevas’s The Agonising Choice he wrote, “….the Holy See might glory in some of the initiatives of Pius XII, who was the first among high Church officials in Rome to recognise the value of family planning and to justify its practice in a series of medical, social, economic circumstances that are precisely those currently invoked today.”

He was spiritual advisor to Marie-Christine von Reibnitz when she was seeking an annulment of her first marriage to wed, in 1978, Prince Michael of Kent, the grandson of his late friend Princess Nicholas. This, along with a photograph of them together at a London party, may have led to rumours years later that he was also assisting Camilla Parker-Bowles to have her Catholic marriage to her first husband, Andrew, annulled. Father dismissed it as “nonsense ….. It was all a pipe dream, but it took weeks to discourage journalists to stop calling me.”

He could also be playful. In reviewing The Secret Archives of the Vatican (by Maria Luisa Ambrosini with Mary Willis), he wrote, “Clergy, for instance, who long to marry, will be happy to learn that these Vatican documents bear trace of the tender and mystical farewell of St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles, to his wife as she was being led away to her execution.”

In 1999 he retired to Rome to the General Curia of the Rosminians at Porta Latina and lived near his sister Cyprienne, Principessa del Drago, widow of Marcello del Drago, marchese di Riofreddo, who had been Chief of Staff of Mussolini’s Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1940 to 1943. He was later the Ambassador to Sweden and Japan.

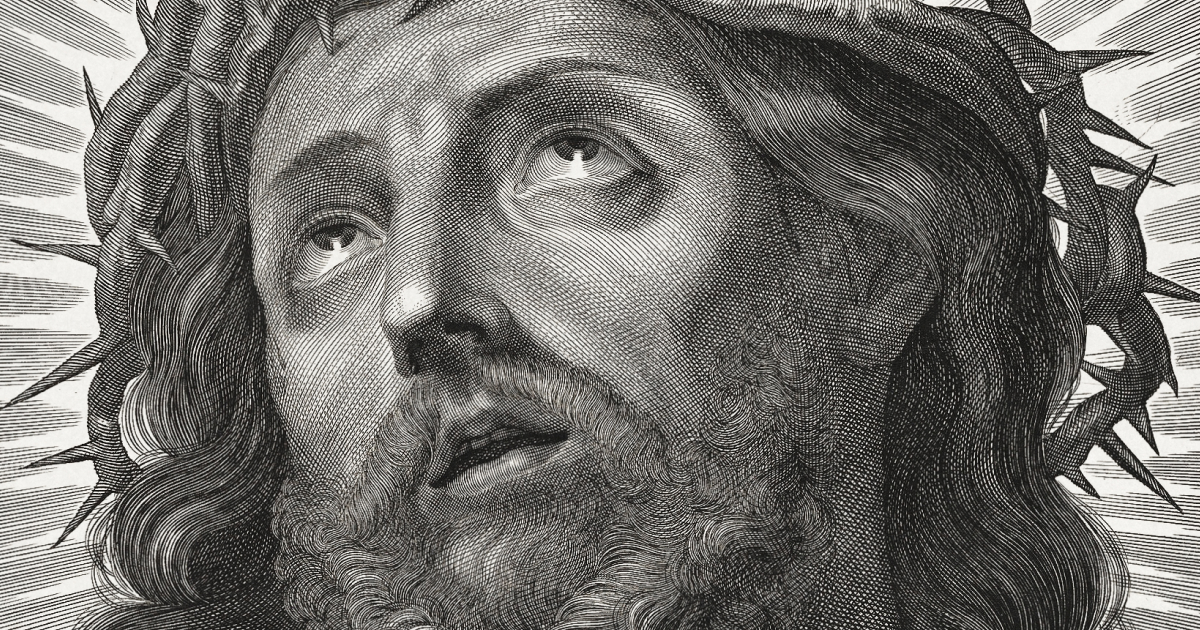

In 2004 Jean-Marie was asked by Mel Gibson (of course, he had never heard of the Hollywood star) to be chaplain to the cast of his graphic The Passion of the Christ, rising each morning to say Mass in the Tridentine rite in a makeshift chapel at Rome's Cinecitta Studios at 6.00 am during the final weeks of filming. More than one conversion took place.

Fr Charles-Roux saw the point of the film as showing what "the Lord went through for our own salvation." Gibson's approach followed the graphic artistic tradition, where painters did not "soft-peddle the blood.” As Father told the New York Times, "The film reminds you of the incarnation and the suffering of God. Christianity can't be a bed of roses." One morning, between takes, Jim Caviezel, the actor who played Christ, came to receive Communion dressed as Jesus crowned with thorns. Even the imperturbable celebrant was shaken.

In 2008, defeated by the steps at Porta Latina, he moved to his sister’s place in Via della Scrofa. The Principessa died in 2010. He was survived by his younger sister, Edmonde, described by The Guardian as “a fearsome arbiter of French literary life.” She was editor of French Vogue (1954 to 1966), arguably Chanel’s best French biographer, winner of the Prix Goncourt and a member of the Goncourt Academy. Widow of a socialist mayor of Marseille, she died in 2016, aged 95.

Jean-Marie had gone to Rome, he said, “to die”. As he told the International Herald Tribune, "It's comforting to grow into a ruin among the ruins of Rome. You don't feel too ridiculous dying in a city like this. Though dying in a city that's called eternal is a bit of a paradox, don't you think?" He lived another 15 years, his charm intact until the end.

Father Jean-Marie Charles-Roux, IC, born 12 December 1914; died 7 August 2014, aged 99.