The latest conclusions of the national Covid Inquiry have hit the headlines, and those who supported lockdown feel vindicated. An expert-led process costing £200 million has broadly endorsed the government’s approach, concluding that lockdown “was right” — and should, in fact, have happened sooner.

But the inquiry has also been labelled as a £200 million pound “I told you so” exercise; never willing to challenge the underlying assumptions of the lockdown strategy. Critics point to the fact that the inquiry uncritically accepted figures based on discredited modelling, and ignored real-world data such as the comparative case of Sweden. They believe that lockdowns not only couldn’t significantly change the mortality rate from an airborne virus, but that they cost lives, wrecked the economy as well as socially, educationally, and psychologically crippling a generation.

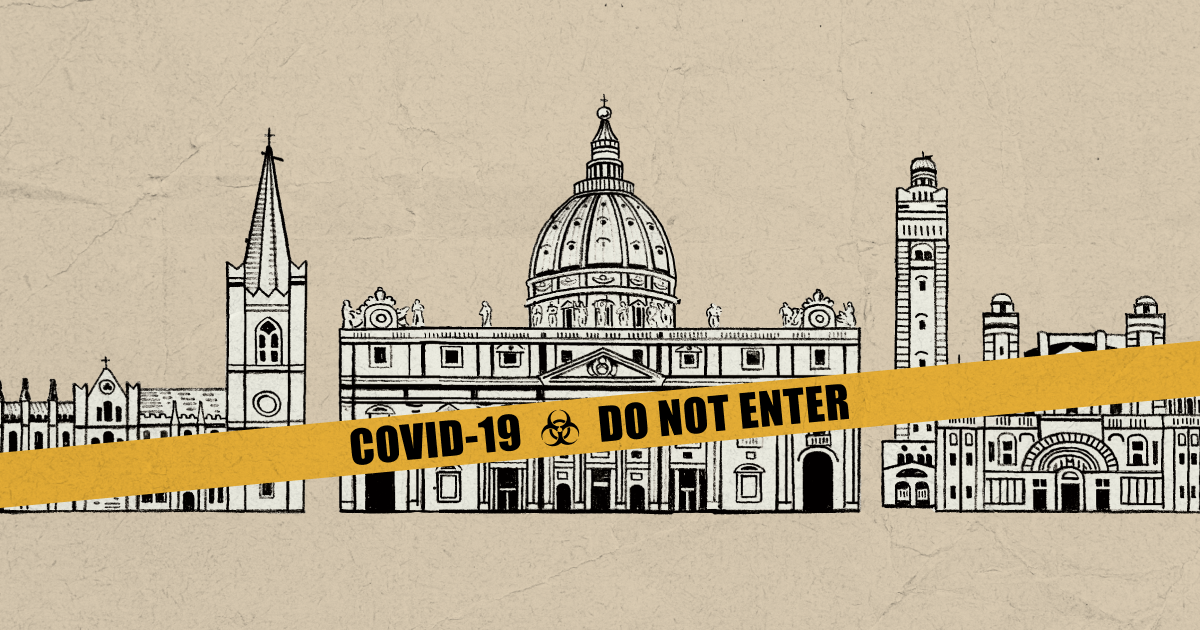

Later modules of the Covid Inquiry will give more opportunity for submissions on the effect of lockdown on Catholic life. But long before any official report appears, the Church faces a pressing question of its own: does the Church need its own internal reckoning? Not a tribunal, but a serious, unafraid conversation about what happened, what was lost, and what must never be repeated.

Like Brexit, the origin, nature, and response to Covid remains an emotive dividing line between generations, sectors of the working population, and even households. Many bishops understandably fear re-opening these wounds. But the wounds exist whether or not we speak of them. If the Church is to serve her people with clarity in the future, she must be willing to examine her response with honesty now.

The response of the institutional Church was panicked, rushed, and arguably incoherent. Surely it’s only appropriate that we learn lessons, draw red lines, consider principle and practice, so that next time (heaven forbid) there is confidence and clarity in our response?

There are three areas that any Catholic retrospective must address.

- Church closure and sacramental provision

Few issues cut deeper than the loss of the sacraments. In both canon law and Catholic theology, grave cause is required to suspend public worship and deny sacramental provision. Yet during the pandemic, confession was severely restricted in many dioceses, and clergy were instructed in some cases not to administer last rites. Many Catholics will never forget the sight of churches locked on Easter Sunday, or the reality of loved ones dying without the sacraments.

The core questions are these: was it justified to remove sacramental provision, which has definite spiritual effects, in order to enforce public-health measures that were uncertain in outcome to physical health? What message does this send about the sacraments, proper worship, and the hierarchy’s confidence in their necessity?

There are also pastoral questions. Should the faithful (and clergy) have been allowed greater freedom to assess their own risks in light of their spiritual duties? What spiritual and social effects flowed from the universal dispensation from the Sunday obligation? Is it even possible to dispense from divine law? And, not least, how much did the mass closure of churches contribute to the dramatic fall in Mass attendance that persists today?

- Church and State: Who Leads Whom?

Nobody argues that Church and state shouldn’t collaborate to mitigate the effects of a pandemic. However, criticism of the Church’s relationship with the government was that it acted like it had no independent authority from the state. And so a key question; what authority should the Church accept the state having over provisions of its life and worship?

Sadly, it was left to individual clergy to establish this principle rather than the Bishops collectively defending it. The clearest example is in Scotland where Canon Tom White took the government to court over church closure and won. It remains striking that this defence of religious freedom arose from an individual priest rather than from bishops acting collectively.

The Bishops of England and Wales did encourage the faithful to write to their MPs to oppose lockdown in 2020. This had a clear effect. Yet it raises the question: why was there no similar resistance before the first national closure of churches? How far did they softly encourage a hard lockdown (that included church closure) in their dealings with the government in order to "minimise risk”? What consultations took place with civil authorities, and what arguments were advanced? Catholics deserve transparency about the Church’s discussions with government, if only so that future decisions can be made with greater clarity.

The Church must be clear about the limits of state authority over worship.

- Scientific Uncertainty and the Church’s Moral Voice

Throughout the pandemic, bishops and clergy often spoke as though scientific questions ( such as the necessity of lockdown or the efficacy and safety of particular vaccines) were settled moral facts. Statements were issued in language that many Catholics understood as direct instructions: a moral duty to observe every restriction, a moral duty to avoid vulnerable relatives, a moral duty to be vaccinated.

One widely circulated statement read:

“The Catholic Church strongly supports vaccination and regards Catholics as having a prima facie duty to be vaccinated… We believe that there is a moral obligation to guarantee the vaccination coverage necessary for the safety of others.”

This is strong language which raises several questions. Why was vaccination framed as a moral obligation rather than a prudential judgement to be weighed by individuals based on circumstances and conscience? Is it appropriate for bishops’ conferences to issue statements asserting that vaccines are “safe and effective,” a claim more properly belonging to scientific authorities? And if such statements later prove mistaken, what pastoral responsibility does the Church bear toward those who suffered adverse effects or lost employment due to mandates?

Behind these questions lies a deeper concern: the blurring of moral and empirical authority. The Church has immense moral and theological authority; she should exercise it boldly. But she must avoid appearing to guarantee empirical claims that lie outside her competence.

The pandemic also revealed confusion about the meaning of the common good, a concept central to Catholic social teaching. Catholics on opposite sides of the Covid divide invoked it to support their positions. The Austrian Bishops went so far as to cite it in support of mandatory vaccination. On one extreme it was used to suggest that individuals shouldn’t be encouraged to voluntarily risk harm to themselves for the good of everyone, while on the other, its use was barely distinguishable from utilitarianism (it’s okay to risk actively harming some to protect the majority, or it’s okay for individuals to be hurt to ‘protect the NHS’). The Church must clarify what the common good truly demands, and what it never permits.

None of these questions are easy. They touch on grief, trauma, and memories some would rather forget. Many bishops, priests, and laity acted out of genuine concern in the face of immense uncertainty, and that must be acknowledged with charity. But love for the Church also requires truthfulness.

A Catholic conversation about Covid is not about blame. It is about clarity: theological clarity about the sacraments, moral clarity about the Church’s authority, pastoral clarity about conscience, and institutional clarity about the relationship between Church and state.

To avoid this conversation would be a failure of care for the people of God. If the Church is to respond with confidence and coherence in the next crisis, whatever form it takes, she must learn from the last.