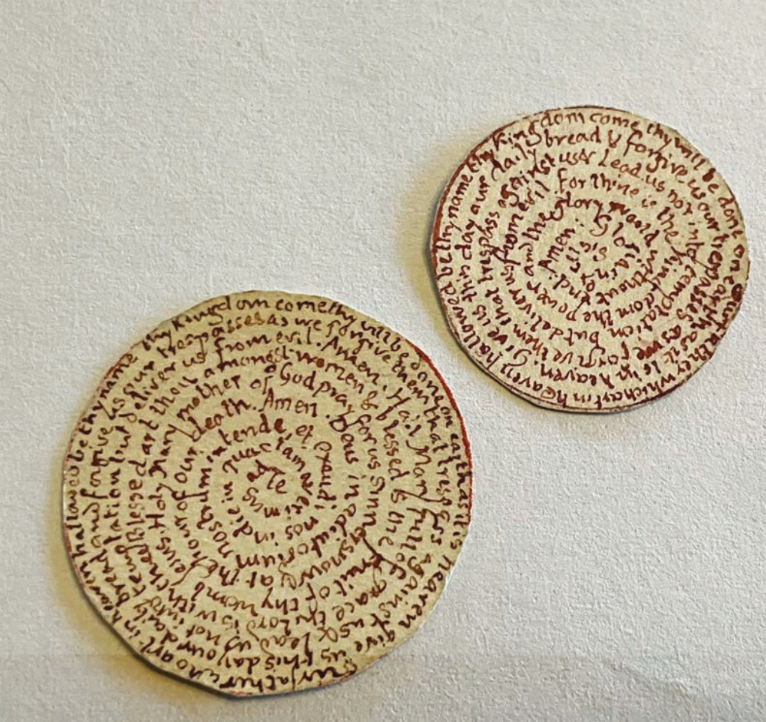

I was brought up a Catholic. I remember praying each night with my grandfather, J. R. R. Tolkien, when I would go to stay with him and my grandmother in Bournemouth, and sensing the certainty of his faith. I still have two circular prayer cards, the size of coins, on which he inscribed the Pater Noster and the Ave Maria in minuscule writing, geometrically following the curve of a diminishing circle: a work of art.

My mother, Faith, was also devout. Towards the end of her life, six years down the slow descent into the dark land of dementia, she told me: “I have faith. That’s my name. I believe that God is looking after me.” I drew immense comfort from her certainty. I still do; but I could not share it. Somewhere in my teens, or perhaps earlier, I lost the spark and have never found it again.

Paradoxically, it didn’t help that I went to Downside School, where I was unhappy. The school monks were practical and the abbey monks were remote. Religion felt strangely absent and had no bearing on my flailing struggle to stay afloat. Deep down, I think I regretted the loss of belief most because I knew that it saddened my mother — although she never reproached me for it, unlike George Eliot’s father. I still possess exercise books in which she painstakingly wrote out prayers and scripture for me, expressing her hope for the person I would become. I lived with a sense that I had failed her, which I often concealed behind irritation.

In 2017, the year of my mother’s death, I began work on a novel about the Spanish Civil War, which expanded over the next seven years to become a two-book portrait of the 1930s set in New York, England and Spain: The Palace at the End of the Sea and The Room of Lost Steps. I knew from the outset that Catholicism was going to be an important element in the story because of the pivotal role that the Church played in Spanish politics and society in that era, but I also found, as I developed the narrative, that religion was becoming integral to the plot as a whole. I came to realise that my own experience was feeding the fictional themes I was trying to explore.

Elena, the mother of the books’ hero, Theo Sterling, is a refugee from the cruel persecution of Catholics during the early twentieth-century Mexican revolution that was so vividly brought to life in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory. The socialist government troops murdered her parents, and her faith is all that she has left to connect herself to them. Her new life in New York is focused on a church in Gramercy Park, attended by fellow exiles who speak Spanish and mourn what they have lost. On a Sunday at the beginning of the story, a British Catholic businessman, Sir Andrew, brings news of the martyrdom of a brave Catholic priest who defied danger to minister to the faithful in Mexico City until his inevitable arrest.

Andrew shows the congregation a photograph of the execution; Elena recognises Father Miguel Pro, who came to her house when she was a girl. She describes the religious intensity with which he responded to the beauty of a sunset, his radiant smile “coming from somewhere deep down inside, from his soul”, transforming her experience of something she’d seen countless times before, and Andrew begins to fall in love with her because the vitality of her faith makes God real to him in a new way. Theo, aged eleven, has the opposite reaction: he feels suffocated by the strength of his mother’s feeling and her need to involve him in its expression, and he is terrified by the death of Fr Miguel, linked in his mind with the crucified Christ on a cross in the church. His jealousy of his mother’s interaction with the glamorous stranger provides him with a way to express his horror and fear through anger.

This moment crystallises the separation between mother and son that neither is ultimately able to overcome, however hard they try. Elena’s faith is emotional and certain, but Theo is “a child of New York City, where everything was man-made and what you saw was what you got”. It is in his nature to doubt and to question, and the gulf between them widens as he becomes politicised in his response to the extreme socio-economic inequalities that he sees in a world gripped by the Great Depression. The Communists seem to be the only people prepared to fight for justice, but to Elena they are the murderers who destroyed her life.

The family moves to England, and Theo is sent to a Catholic boarding school where he falls under the spell of Esmond, a charismatic Communist. When writing this section of the books, I was concerned that I could fall into the trap of satire and turn my fictional school into a vehicle for rewriting my own history, but I think that awareness of the pitfalls kept me honest, and the school provided me with the opportunity to portray a humane, thoughtful Catholicism in the person of Theo’s housemaster, Fr Laurence. It serves as an antidote not just to Esmond’s communism but also to the extremism that Theo encounters when he moves to Spain.

The deterioration of family relationships reaches its climax in Spain and provides a lens through which I sought to explore the role of religion in the escalating conflict there between left and right. For Elena, the Mexican and Spanish Churches are the same, and she cannot see that the one is a victim of persecution, whereas the other is immensely rich and identifies with the ruling class — the army and the great landowners who own ninety-nine per cent of the land — while the working classes live on the edge of starvation. The poor, especially in the south, have turned to anarchism: a utopian creed that imagines a world without God or state.

Theo experiences firsthand the anarchists’ hatred of the Church when the army tries to overthrow the government in Barcelona. He sees the desiccated, dug-up corpses propped up against church pillars — “proof that eternal life was a lie peddled by the Church to keep the common people in thrall” — and he tries to intervene when the anarchists set up a machine gun to murder the Carmelite friars who have been sheltering soldiers in their monastery.

He cannot fathom the hatred — this red terror soon answered by a white terror unleashed by Franco’s Army of Africa as it marches on Madrid, perpetrating atrocities on the way. But the violence never blinds Theo to the facts that the army has risen to overthrow a democratically elected government that had been trying to reform an unjust society, and that it is supported by Mussolini and Hitler and the Church in Spain. He feels unable to stand aside and do nothing, and volunteers to fight with the International Brigades.

In these two novels I have tried to portray the Church in the 1930s in its various guises, and, building on my own experience, to explore different responses to belief through the medium of family relationships. I hope that they may fuel readers’ interest in a rich period of history which now seems part of the remote past, eclipsed by the world war that followed it and changed everything forever.

Photo: an image taken during the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s showing Republicans fighting on a road in an unidentified place (Photo credit STF/AFP via Getty Images)

Simon Tolkien lives in Santa Barbara, California. The Palace at the End of the Sea and The Room of Lost Steps (Lake Union, £ 13.99) are out now