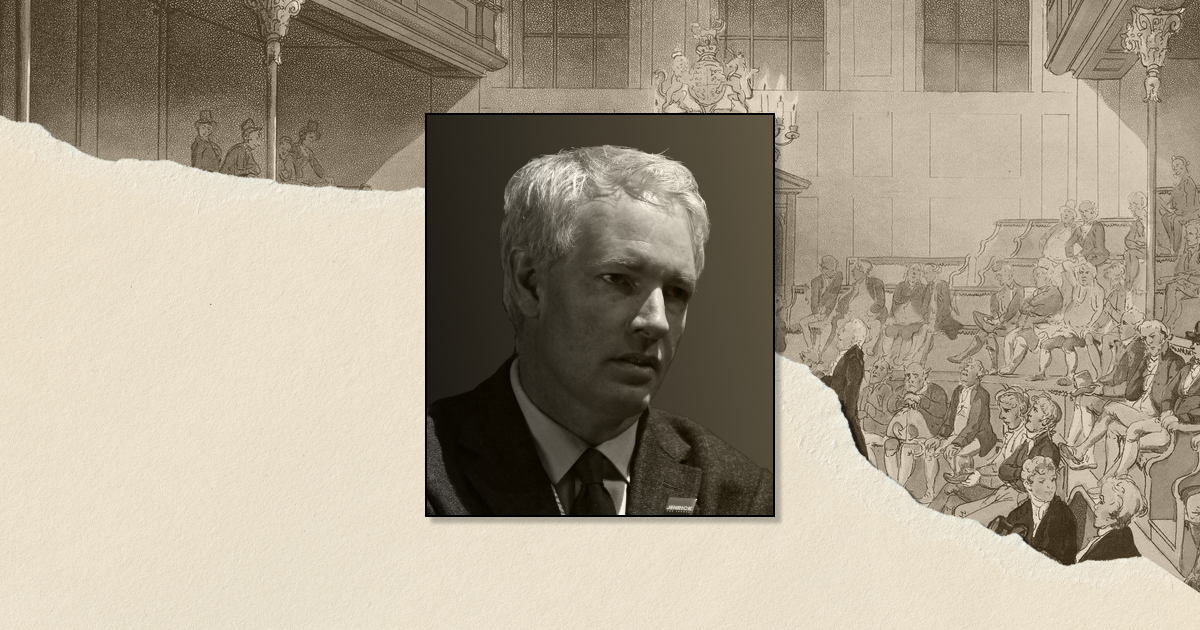

Last month, Danny Kruger, Member of Parliament for East Wiltshire, stood in an empty Commons chamber and said what few in this country today would dare to suggest aloud: Britain needs a Christian revolution. Not a throwback, not a theocracy, but a moral reawakening rooted in the religion that built this once-great nation.

His own colleagues – who swear by the King James Bible and pledge allegiance to God’s servant on Earth, King Charles III – couldn’t be bothered to show up for appearance’s sake.

But Kruger wasn’t speaking for the political class. He was speaking against its failures.

Despite the best efforts of secularists and disbelievers, Britain is still a Christian nation. One that still eats fish on Fridays, shuts the shops early on the Sabbath, and parrots ‘God Save the King’ when international sporting tournaments come around.

For decades, Britain has run on the dying embers of Christian ethics while decrying the source material. We want compassion without conviction, rights without responsibilities, communities without commitments. We worship tolerance while being intolerant of belief. And now, the cracks are showing.

Loneliness is an epidemic. Family structures are falling apart. Crime, mental health crises, nihilism — the data tells plenty, but everyone can feel it. A vital connective organ seems to have disappeared in the British body.

Britain is still, by appearance, a global power. But we are materially rich and morally rootless.

Kruger’s speech cut through this fog with rare clarity. He wasn’t moralising; he was diagnosing. Britain is adrift not due to policy failures (though there are plenty, especially under the current Labour regime) but because we’ve abandoned the moral architecture that once held us together.

The Church, once at the heart of the nation’s consciousness, has been pushed to the margins. In its place? A hollowed-out secularist shell of the Empire it once was, with no power to inspire, heal or endure.

Kruger was right to suggest that the State cannot fix what is ultimately a spiritual problem. The welfare state, though necessary, will not replace parenthood. Curriculum reforms will not substitute lessons of morality. Economic growth, for all its virtues, can never alone make a nation prosperous.

Of course, progressive society will scoff at the notion. They will argue that the British Isles have outgrown theological puritanism, that civilised society has no need for the archaic influence of Christianity. They will say that Britain has evolved past religious constraints, and that the future is built on secularism, multiculturalism and diversity.

But look around. Is it working? Do today’s pieties bring peace, joy, resilience? Or are we angrier, more fragmented, more fragile than ever?

Kruger is not calling for Bible-thumping blue laws or forced religiosity. He is reminding us that freedom isn’t sustainable without virtue — and that virtue doesn’t grow in a vacuum. For centuries, Christianity taught us that we are flawed but loved. That life has purpose. That we owe something to each other, and to something higher than ourselves.

The Christian faith shaped our laws, our liberties, even our language. Like it or not, British history is a Christian one, and Christianity is an undeniable foundation for all that we have today.

Remove that foundation, and what remains? Technocracy. Tribalism. Therapy-talk. We treat the symptoms, never the disease. We legislate endlessly but refuse to speak of what’s good, true or beautiful — as if that’s someone else’s job.

It isn’t. And Kruger dared to say what most MPs won’t: that our national decline isn’t just economic or political — it’s spiritual. He said it plainly, in an empty chamber, to a country that doesn’t want to hear it.

But sometimes, the truth starts as a whisper. Let’s hope more Britons start listening before the decline of our nation becomes irreparable.