A recent report from the Barnabas Society found that 700 Anglican clergy and religious converted to the Catholic faith between 1992 and 2024. The conversions resulted in 491 ordinations to the sacred priesthood and, considering that conversion follows a period of formation before those who wish to receive Holy Orders, that number is expected to rise.

The ordinations thus far account for 35 per cent of the combined diocesan and Personal Ordinariate priestly ordinations from 1992 to 2024. It is not hyperbolic to describe this as a major shift in the religious tapestry of our time, with effects felt across the communities these men served. The United States saw similar patterns, with an estimated 125 Roman Catholic priests ministering across the country who were former Episcopalians.

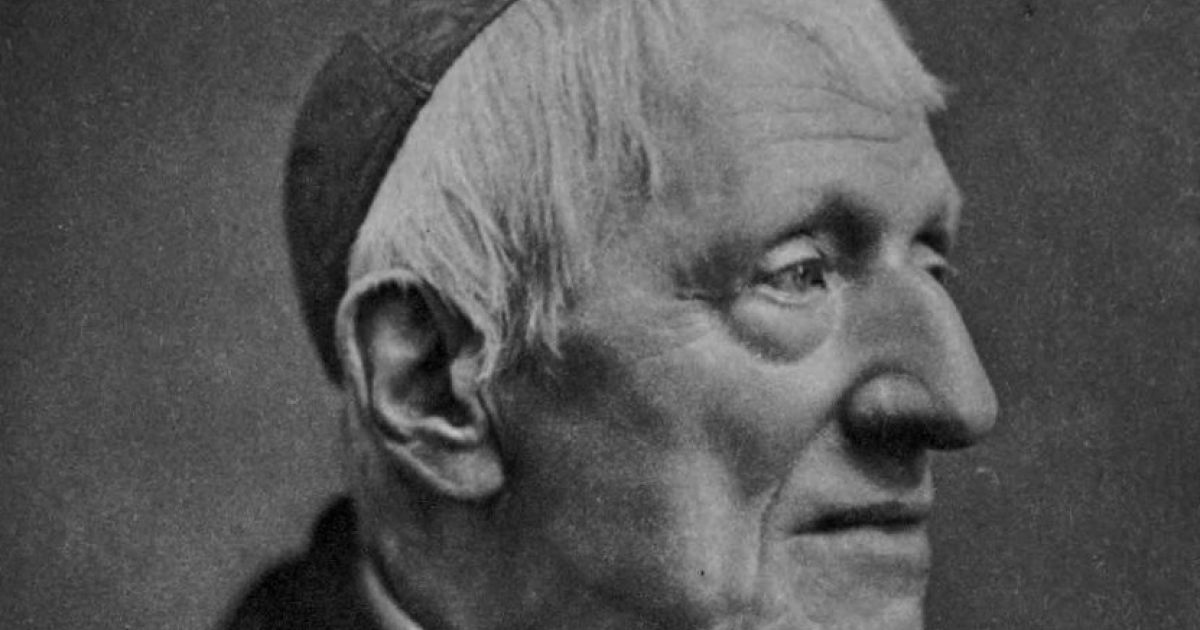

Seeking a source for this ecclesiastical phenomenon, it is important to note the enduring influence of the 19th-century convert John Henry Newman. A convert, provost of the Birmingham Oratory, cardinal, saint, and later declared a Doctor of the Church, he is among the most eminent of the Victorians, despite being rebuffed in favour of his contemporary Cardinal Henry Edward Manning in Lytton Strachey’s ‘Eminent Victorians’. From evangelical to High Churchman, Newman’s journey spanned a wide breadth of Protestant experience.

In his evangelical years in his early twenties, Newman learned to treat the truth claims of Christianity seriously. He addressed the theological questions of his time in a forthright manner, such as Baptismal Regeneration, though often fell short in his conclusions. He believed the pope to be the Antichrist and was preoccupied with what the numerology of Daniel and Revelation might suggest about the fate of the world, allowing parts of his faith to be directed by prejudice and a desire for novelty rather than guided by the inheritance of the Church Fathers.

Still, even in his evangelical years, Newman had a strong sense of the responsibility of his Anglican clergy identity. Writing in his diary upon being ordained deacon, the young Newman recorded, “It is over. I am Thine, O Lord.” His theological wandering during this period also led him to positions he would later rely on. Being taught Apostolic Succession during his time at Oriel College, Oxford, which he later described as a teaching he was “somewhat impatient of,” he came to a fuller understanding of Tradition, concluding that “the Bible was never intended to teach doctrine, but only to prove it.”

These instincts, alongside his intellectual disposition and the influence of John Keble and Edward Pusey, led him to High Church Anglicanism, an ecclesiastical movement Newman helped build and which continues to the present day. The movement led a quest to make Anglican belief and practice closer to Roman Catholic patterns. In his own words: “The Anglican Church must have a ceremonial and a fullness of doctrine and devotion if it were to compete with the Roman Church”.

This recognition of Catholic strengths and the Tractarian openness to Tradition contributed eventually to many conversions, notably through the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, founded in 2011 for former Anglicans receiving Catholic Holy Orders. Newman’s fellow Tractarians, named after the ‘Tracts for the Times’ pamphlet series, initially intended to remain within the Anglican Communion, as Keble did, but their openness to Catholic belief led many later to accept Catholicism fully.

Saints’ legacies rely on their teaching, the example of their lives, or a combination of both. Newman finds himself among those whose teaching and life both shaped his legacy. His theological framework found in works such as the ‘Grammar of Assent’, ‘An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine’, and his 1864 ‘Apologia’, provided a recurring influence on Anglican and Catholic thought.

Poverty, funding shortfalls, conflict and legal setbacks marked large parts of Newman’s Catholic life. In the early years of his Oratory, almost none of the vocations persevered and the period included internal tensions, notably in his early relationship with William Faber. During his tenure as the founding rector of the Catholic University of Ireland from 1851 to 1858 the university struggled to attract sufficient students, failed to secure a charter or government recognition, and remained chronically under-funded. He was also convicted of libel in a trial against Giacinto Achilli, a former Catholic priest and morally defunct man who had become an Anglican preacher.

Yet Newman’s later years brought renewed prestige. In 1878 he became the first Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, and in 1879 Pope Leo XIII created him cardinal. His influence increased further after his death, particularly on how the Catholic Church understands conscience.

Newman’s life, despite setbacks, was marked by a repeated willingness to pursue truth at personal cost. It was this example, as well as his theology, which led many Anglicans to find their home in the Catholic religion. His legacy shone through particularly clearly in 2013 when 12 Anglican nuns left their convent to become Catholic. Three of the sisters were in their eighties and three in their seventies. Explaining her decision, one of the elderly sisters simply said: “I want to die a Catholic.”

It has been a gift to the Catholic Church to receive so many converts in recent decades. However, care should be taken to remember the deep personal sacrifice that shaped these journeys. Many moved in the legacy of Newman, who left security and prestige at 44 to convert to an alien religion, and long may that legacy continue.