When Pope Leo XIV attended the Divine Liturgy, his presence beside Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew reaffirmed Rome’s commitment to Christian unity at a moment when secular governments in East and West are engaged in closed-door political conflict.

During his homily, Patriarch Bartholomew emphasised the spiritual unity of the two Churches while acknowledging the formidable theological barriers that continue to obstruct communion between the Eastern and Western Christian traditions.

“As successors of the two holy Apostles, the founders of our respective Churches,” he said, referring to Peter and Andrew, “we feel bound by ties of spiritual brotherhood.”

The two holy apostles invoked by the Patriarch were Peter, who became the first Pope, preached in Rome and was martyred there, making that city the centre of the Western Church, and Andrew, whom Constantinople later claimed as its own founder by virtue of establishing the Diocese of Byzantium, which grew into a principal spiritual centre of the Eastern Christian world.

The Patriarch also noted that “we can only pray that issues such as the filioque and infallibility will be resolved so that differences in understanding may no longer serve as stumbling blocks to the communion of our Churches.”

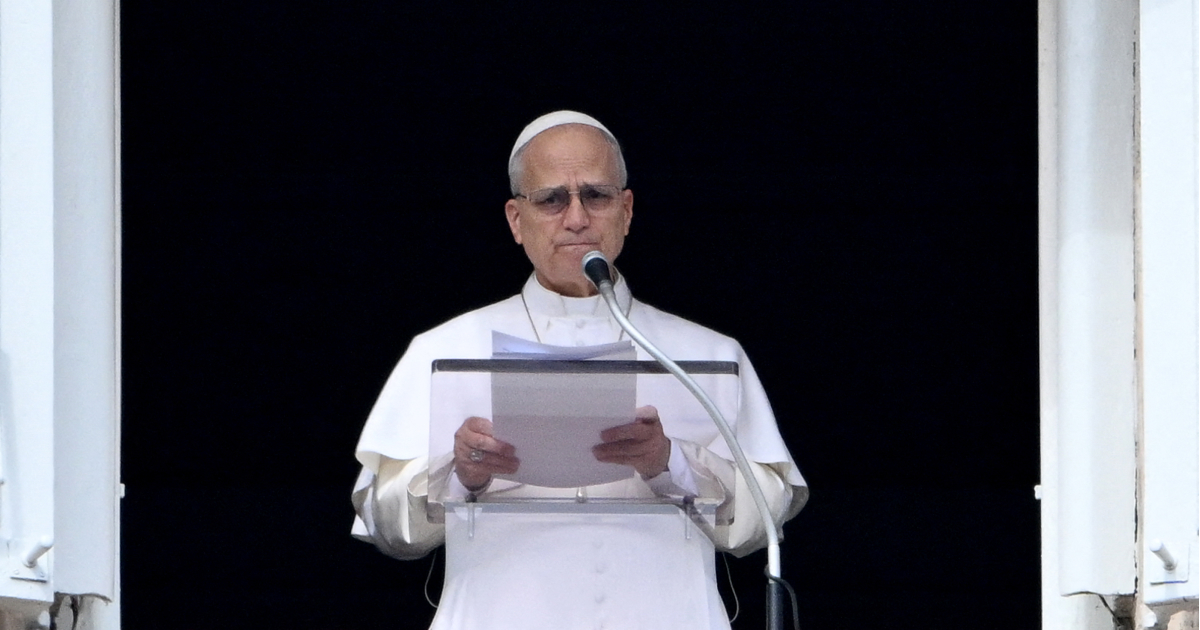

Addressing the packed cathedral, Pope Leo described the past six decades of dialogue as “a path of reconciliation, peace and growing communion,” adding that cordial relations are sustained through “frequent contact, fraternal meetings and encouraging theological dialogue.” He reiterated that the pursuit of full communion remains “one of the priorities of my ministry as Bishop of Rome.”

After the liturgy, the Pope and Patriarch stepped onto the balcony above the courtyard to bless the faithful who had gathered despite heavy rain. Among the hierarchs present was Patriarch Theodore II of Alexandria.

Patriarch Bartholomew appeared at Pope Leo’s side for nearly every major moment of the visit, from the meeting with President Erdoğan in Ankara to the commemorations at Nicaea and the Mass celebrated for Turkey’s Catholic communities.

The lifting of the anathemas in 1965, once described as a spiritual spring, set in motion the theological work that continues through the Joint International Commission. Although progress has slowed amid internal divisions within Orthodoxy, both leaders signalled their resolve to sustain the dialogue.

The Patriarch’s homily, however, conveyed more than a call for unity. It suggested an expectation that Rome, rather than Constantinople, must make the decisive doctrinal concessions if communion is to be restored. By identifying “the filioque”, the Catholic belief that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and Son, rather than from the Father alone, and “infallibility”, the Catholic belief that the Pope is incapable of error in pronouncing dogma, as “stumbling blocks” for communion his words read less like fraternal diplomacy and more like a measured challenge to the parameters of Catholic ecumenism. He points directly to the doctrines over which communion fractured, signalling a belief that responsibility for the rupture lies primarily with Rome.

Rome has shown legitimate liturgical flexibility concerning the filioque—omitting it at Nicaea, and permitting Eastern-rite Catholics to profess the Creed without it in keeping with the received tradition of their rites—but papal infallibility cannot be relegated to a negotiable adaptation or cultural variance. If it were, it would be ceasing to profess a dogmatic definition solemnly articulated by an ecumenical council, Vatican I.

The Patriarch’s insistence that unity must not become “absorption or domination” clarifies that the Orthodox concern remains the risk of doctrinal universalism overwhelming local ecclesial identity.

The central dividing line is not whether ecumenical warmth endures, Leo’s attendance demonstrates that it does. The core question is whether Catholic-Orthodox dialogue can progress without requiring either Church to revise doctrines that form constitutive elements of apostolic and conciliar identity.

Unity cannot require the dissolution, repeal or abandonment of doctrines that each Church professes as integral to its own dogmatic integrity. Warmth may open a door once closed, but doctrine still holds the key. There is no plausible path to full communion that requires Catholicism to cease professing the doctrines by which it defines its own conciliar and apostolic identity.